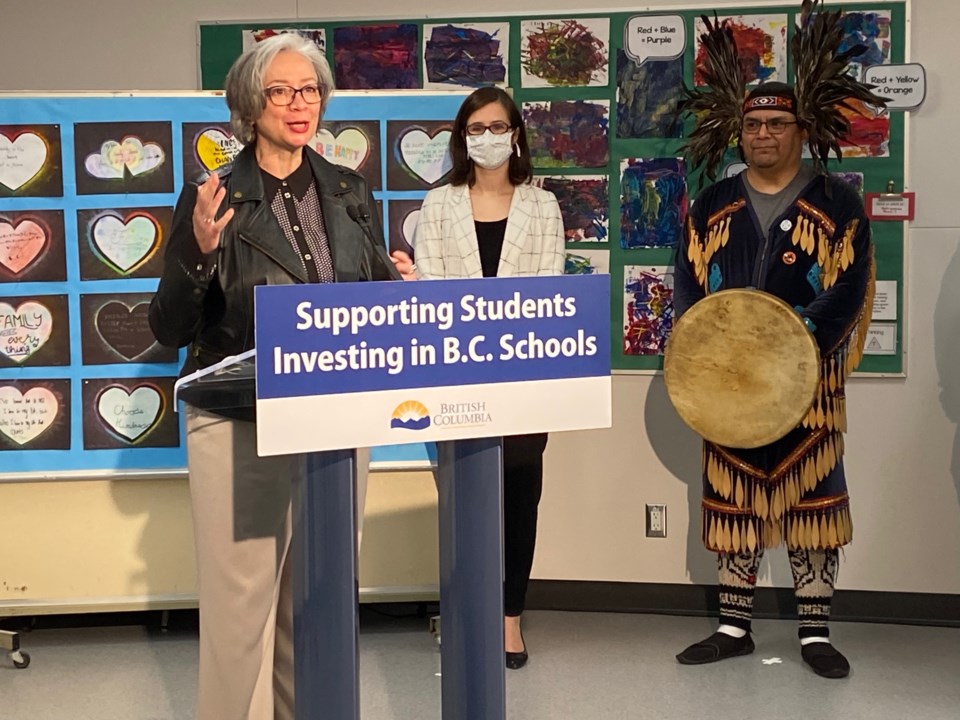

To pay for new schools, B.C.’s education minister Jennifer Whiteside says her ministry is actively looking at potential fee increases for new residential developments.

“That is an issue the ministry is looking at right now. We’ll be talking to school districts about that issue,” said Whiteside.

School site acquisition fees haven’t changed since they were implemented in 2000, despite calls from school trustees in districts like Surrey to review them.

The fees are meant to create a system where new residents to a community pay for new schools, as opposed to downloading costs on existing residents who have already paid for existing schools.

They are currently capped at $600 per new condo unit, $800 for a townhouse and $1,000 for a detached house.

As populations climb, new schools left in limbo

The fee cap is a problem for school districts like Richmond, which expects to need a new school in its City Centre within the next decade. When the Richmond Board of Education proposed to hike the developer fees to the provincial maximum last month, it was among the last in Metro Vancouver to do so. They go into effect at the end of May.

Richmond city planners estimate about 300 new townhouse units would add another 50 school-age children to a neighbourhood. If, for example, 3,000 new townhouses were built, something like 500 new kids would need a spot in a school, but the acquisition fees would generate just $2.4 million.

The land for the new school in Richmond's City Centre is expected to cost $75 million alone.

“It’s the same for the entire province,” Richmond Board of Education chair Sandra Nixon told Glacier Media. “They need to look at this area, because the reality is, what we’re taking from those fees is a drop in the bucket in terms of what we would need to purchase land.”

Compounding the problem, said Nixon, the ministry continues to expect districts to use capital reserves to pay for upgrades that it deems to be discretionary.

Richmond received $41 million from the sale of a high school in 2013. That was supposed to be used for the downtown school, but after several discretionary expenditures, including $12 million worth of HVAC upgrades in existing schools during the pandemic, the district has only $14.8 million in the capital reserve.

Despite a decade-long building boom in the city, Richmond has collected just over $8 million from School Site Acquisition Charges.

“It’s kind of a catch-22 for districts. It’s difficult to hold on to surplus funds, like the sale of Steveston [Secondary School],” said Nixon. “If school districts have funds to contribute, we will be asked to contribute. If we don’t, well there’s still a need for schools.”

In a tricky balancing act, with some of the district's funding also used to offset deficits in operational funding, added Nixon.

Whiteside says COVID-19 delayed government's school agenda

Prior to taking power in 2017, the NDP was critical of the BC Liberal government for forcing cuts on districts.

Whiteside said her government is spending record amounts on education but blamed a lack of prior investment to explain the continued pressures.

She also cited the arrival of 100,000 new residents to B.C. last year as an added and unforeseen pressure on school systems.

When asked why the ministry hasn’t increased fees for the developments that are supposed to house those newcomers, Whiteside said the COVID-19 pandemic has delayed a number of projects in the ministry. She offered no timeline on when districts may expect a higher ceiling to charge developments fees to fund new schools.

Acknowledging Richmond's move to hike the school site acquisition fees, Whiteside said provincial changes are “actively under consideration” and that her government will be consulting school districts.

In an email, Whiteside pointed to what she described as a success story when in 2018, the government invested $7.6 million to purchase land in Langley's Yorkson neighbourhood. The Langley School District provided $1.7 million from the fees.

A June 15, 2021, report to Langley’s board shows the district needs $182 million for land to cover 16,382 eligible development units. The charges were first designed to cover 35 per cent of those costs. But to do so the district would need to charge 4.87 times more than what the province allows under current legislation. If those fees were realized, each new house would pay $4,871 instead of the current $1,000 maximum.

The same report shows Surrey, New Westminster, Burnaby, Maple Ridge and Coquitlam have also raised fees to their maximum level.

A race against inflation

In January 2020 the B.C. School Trustees Association (BCSTA) called on the province to eliminate the cap and allow districts to create a formulaic charge.

“Inflationary and speculative pressures tied to rapid growth have increased land values significantly,” wrote the association to then Minister of Education Rob Fleming who told Glacier Media in March 2020 the ministry was reviewing the fees.

“Delays in purchasing land which will eventually be needed have resulted in millions of dollars of increased costs, some sites more than doubling in value in less than two or three years.”

That was before pandemic spending spiralled inflation to historic highs.

Developers, meanwhile, claim the development cost charges harm affordability (at least for new home buyers) as the costs are passed on to consumers.

For a provincial government that has repeatedly said it wants to improve housing affordability for British Columbians, weighing a fee increase to help build new schools adds another variable.

But according to the BCSTA, the relatively small increase to the overall price “would be minimal.”

“[It would be] reflected in the bottom line of the development community.”

With files from Maria Rantanen/Richmond News