When B.C. Premier John Horgan stepped in front of a Council of Forest Industries meeting last month, he had a straightforward message: build a forestry sector that “works directly with Indigenous Nations.”

In April 2020, a landmark study recommended immediately deferring old-growth logging in B.C. until a long-term solution for its future could be found. More than a year later, it’s not clear how the province intends to put that vision into practice at a time many scientists and Indigenous leaders warn there’s not much time left.

“They're talking out of two sides of their mouth on this,” said Squamish Nation Coun. Khelsilem. “They're saying that they want to work collaboratively with nations and they're gonna consult us on resources.

“But the timeline on it means that while that's happening — and it's taking, you know, months and years to complete — the logging companies are moving into all the old-growth areas right now.”

Hundreds of years of commercial logging have decimated British Columbia’s forests. Despite skyrocketing timber prices, many lumber mills across the province have been forced to shut down. As timber companies continue to log some of the last remaining patches of ancient rainforest in the province, both environmentalists and the scientific community say we’re shooting ourselves in the foot: old-growth trees capture an astounding amount of carbon and support a complex ecosystem that can’t be replicated in industrial tree farms.

First Nations communities have fallen on both sides of the argument. Several Indigenous communities have quietly demanded the B.C. government immediately defer logging its oldest trees, warning it “will ultimately bring about our physical destruction.” At Fairy Creek, where multiple arrests along a blockade have continued to draw the media’s spotlight this week, the Pacheedaht First Nation have said old-growth activists are “not welcome.”

A hundred kilometres across the Salish Sea, another Indigenous nation has been locked in a protracted fight to protect a swath of old growth sacred to their people. They fought back, and in March, won — protecting a 70.9-hectare cutblock of forest from immediate destruction.

As old-growth forests dwindle across the province, their success shows what it takes to walk another path and protect B.C.’s last arboreal giants.

Elphinstone Logging Focus campaigner Hans Penner at the base of a large yellow cedar in Dakota Bowl. By Ross Muirhead

Elphinstone Logging Focus campaigner Hans Penner at the base of a large yellow cedar in Dakota Bowl. By Ross MuirheadA LONG HAUL

For the Squamish Nation, Dakota Bowl is one of its last untouched tracts of forests.

Rising up the slopes of Elphinstone Mountain on the Sunshine Coast, its high-elevation yellow cedar forests have been described as a “living museum."

Prized for its strength and softness as clothing material, some West Coast Indigenous communities would travel great distances to harvest the inner bark of the yellow cedar; some believed the high-elevation trees possess supernatural qualities.

Khelsilem said his nation’s push to protect the 70.9-hectare cutblock required years of research and policy work. He points to 2003 when the nation developed a land-use plan that sketched out how it wanted to use forested lands. Later, the nation sent out its own experts in archaeology, cultural heritage and the environment.

Archaeologists have found evidence that dozens of old-growth trees had been used by the First Nation dating back hundreds of years — in the end, 77 so-called “culturally modified trees” would be mapped in the forest.

Whereas at Fairy Creek, environmentalists and the Pacheedaht First Nation find themselves on opposites sides of the blockade; at Dakota Bowl, both the Squamish Nation and the environmental group Elphinstone Logging Focus (ELF) worked toward the same goal, raising the stakes for the provincial government every year.

Over the past decade, ELF collaborated with Squamish elders, UBC professors and a filmmaker to get the word out that the ancient forest was under threat. A February 2021 study commissioned by the group found that if Dakota Bowl was logged, 30 black bear tree dens could be lost.

Finally, after a decade of relentless work, the Squamish Nation announced March 1, 2021, that it had reached a new deal with the province to take the Dakota Bowl off the timber harvesting auction block. Its future had some breathing room.

For Khelsilem, the nation's victory is a "minor success."

"The vast majority of old growth in my territory has been logged already — there's very, very little left," he said.

He's now eyeing how to scale up Squamish's minor success across the province. But gathering the research required by the B.C. government takes time and money many smaller First Nations don't have.

That leaves Indigenous leadership in the tough position: work with logging companies to support communities left behind by generations of colonialism, or protect a forest with no promises for the future.

“In some nations, their territories are much, much larger than mine,” he said. “They're dealing with a significant amount of old growth that needs to be protected. It's a lot of territory to cover.”

“We need time to talk. You know, we can’t be logging and talking at the same time.”

Khelsilem (Dustin Rivers), right, elected councillor and spokesperson for Squamish Nation, embraces Tsleil-Waututh Nation councillor Charlene Aleck in celebration before First Nations leaders respond to a Federal Court of Appeal ruling on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Khelsilem (Dustin Rivers), right, elected councillor and spokesperson for Squamish Nation, embraces Tsleil-Waututh Nation councillor Charlene Aleck in celebration before First Nations leaders respond to a Federal Court of Appeal ruling on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl DyckWHY OLD GROWTH MATTERS

In B.C., old growth is classified as anything older than 250 years old on the coast and 140 years in the Interior, a difference largely due to ecosystems dominated by natural fire cycles. In coastal rainforests, researchers have found trees with lifespans dating back to nearly the height of the Roman Empire.

When those ancient trees are harvested, a huge proportion of that carbon, as well as carbon stored in the soil, is immediately lifted into the atmosphere — the life of an up to 1,800-year-old air filter and heart of a complex ecosystem snuffed out.

The fate of old-growth stands has global implications.

Globally, forests scrub a third of all human-caused carbon dioxide emissions from the atmosphere every year. But not all trees are made equal.

Hundreds and sometimes thousands of years old, old-growth trees support a massive underground network of fungi, guiding nutrients and water between multiple species. It's not just the "hugely valuable" role they play in maintaining forest biodiversity, said forest ecologist Rachel Holt.

A study last year out of Washington found that of over 600,000 trees surveyed, the largest three per cent stored 42 per cent of all the forest’s carbon stored above ground. Others have estimated the top one per cent diameter trees store half the carbon in all world forests, though other studies have tempered that estimate.

Whatever the number, said Holt, when it comes to climate change, “We have forest stands in British Columbia that hold some of the highest sources of carbon of any forest.”

What’s needed to protect those ancient trees, concluded a province-commissioned Old Growth Strategic Review in April 2020, was a “paradigm shift” putting ecosystems at the centre of forestry practices.

Since then, the B.C. government has been largely quiet in public.

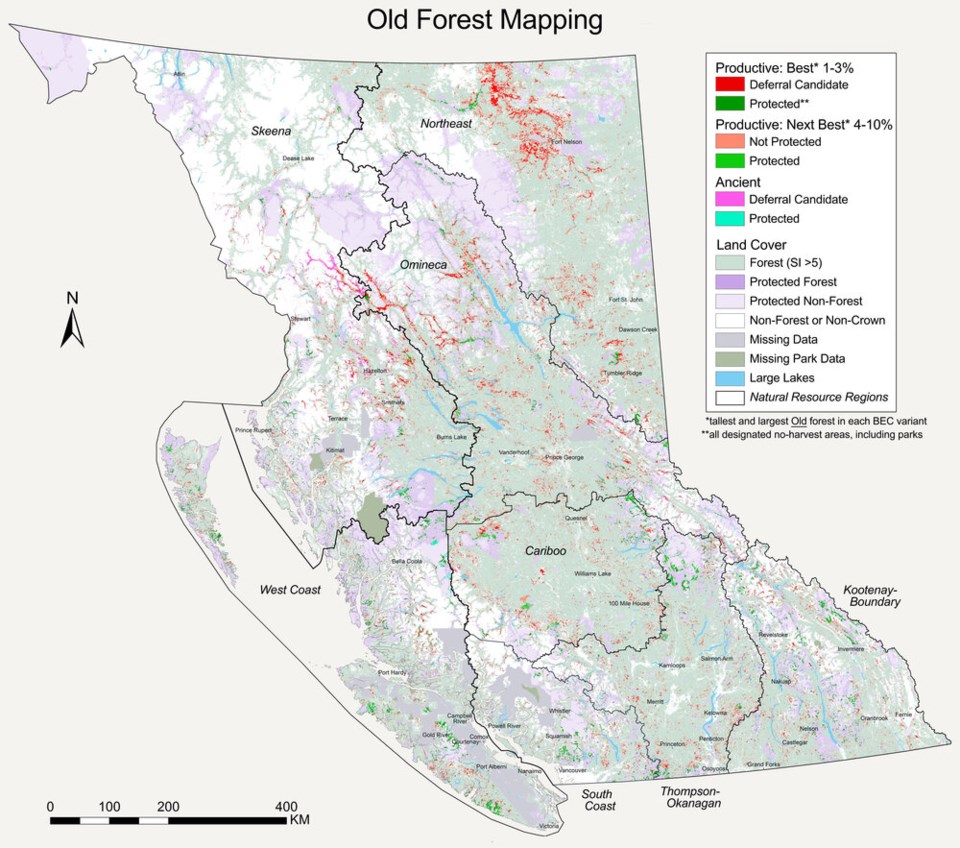

This week, Holt along with forester Dave Daust and researcher Karen Price, took it upon themselves to produce a series of maps tracing the location of the highest value, most at-risk old-growth forests in the province.

“There hasn't been any public release of anything from government. So we just decided to go ahead and map what the panel said you should defer harvesting,” said Holt, who released the maps as a clear path forward to conserve B.C.’s last big trees.

Based on publicly available provincial data, Holt and her colleagues don't dispute the province’s conclusions that B.C. has roughly 13.2 million hectares of old-growth forest.

“But the thing that they don't say, and that our report looked at, is that 80 per cent of that old growth is in ecosystems that only grow small trees,” she said. “It tends to have way lower carbon stored.”

Picture smaller trees in bog forests on the coast, said Holt, stands that are rarely at risk from logging. In contrast, only three percent of the remaining old-growth forest falls in the big-tree category found at places like Fairy Creek and Dakota Bowl.

Many of those ancient forest groves meet the province’s own criteria to defer old-growth logging, what Holt describes as “just a step on the way to another solution.”

By mapping roughly 1.3 million hectares of forest with the highest ecological value, Holt and her colleagues said they're trying to "kickstart the conversation around old forest deferrals" and prompt the province to ward off destruction of very high-value ancient forests, "irreplaceable in the true sense of the word."

Three independent forestry experts released maps tracing candidate areas to defer commercial logging of B.C.'s oldest and biggest trees. By Rachel Holt, Dave Daust, Karen Price

Three independent forestry experts released maps tracing candidate areas to defer commercial logging of B.C.'s oldest and biggest trees. By Rachel Holt, Dave Daust, Karen PriceGETTING TO THE TABLE

Last week, both Holt and Khelsilem presented their work on old-growth deferrals to the BC Union of Indian Chiefs. Both said they were well received by leaders, many asking for more data.

According to a spokesperson from the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, the province received Holt’s maps May 13, and said it's analyzing them and will continue to work with the researchers.

“We are exploring further deferral areas through engagement with Indigenous Nations, and in alignment with the old-growth report,” wrote the ministry spokesperson in an email.

But for Holt and Khelsilem, they say those deferrals need to come immediately, if only to buy time for B.C.'s last ancient forests.

Long-term, Holt said the future of forests in this province is synonymous with the future of jobs for many Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

The low-hanging fruit, she said, is shifting away from a volume-based logging industry and moving toward something more sustainable.

That means creating furniture, for example, instead of shipping out raw logs, or investing in a tourism sector that won’t wipe out the natural resources it relies on.

“We are world-famous for these forests,” said Holt. “Unfortunately, just like climate issues, the longer we wait, the harder it is to do the transition.”

VIDEO: The latest from the Fairy Creek blockade from Glacier Media’s Alanna Kelly

With files from Sophie Woodrooffe, Keili Bartlett and Alanna Kelly