This is a tale of two graves.

Both bear the name of Alexei Romanov, son of Czar Nicholas II who abdicated during the Russian Revolution.

Alexei was the czarevich, heir to the throne until the 1917 abdication.

The family — with Empress Alexandra, Alexei’s four sisters and their staff — was executed in Siberia on orders from Vladimir Lenin, first leader of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, communist Russia.

However, a Burnaby woman says her husband escaped that 1918 massacre and lived quietly in Canada until his 1977 death.

This is a tale of a loving wife telling her husband’s story, a tale of palaces and staggering wealth, a tale of revolution and a family massacre. It’s a mystery involving DNA technology using European royal family members’ genetic material.

The graves

One grave is beside a hedge in Burnaby’s Ocean View Cemetery. The Russian Imperial Family’s double-headed eagle crest adorns the marker.

It reads, “Romanov, Alexei. Grand Duke. Sovereign Heir.”

The other rests in a gold-spired cathedral in St. Petersburg, Russia, on an island opposite the czars’ glittering Winter Palace. Nearby are Peter the Great and Catherine the Great’s gold and marble tombs.

DNA experts say the remains in that grave are Alexei’s. So too does the Russian Orthodox Church, which made the family saints.

Burnaby's Sandra Tammet-Romanov says otherwise. She’s been arguing passionately for recognition of husband Alexei Tammet-Romanov’s claim for years.

She’s not interested in the family fortunes or titles, she tells Glacier Media. She just wants the historical record set straight.

The 83-year-old says she’s been warned off numerous times, and that powerful forces are in play that could be dangerous to her or others in her husband’s claim.

The massacre

Before moving to Tammet-Romanov’s story, let’s backtrack a century.

History records show that communist revolutionaries gunned down the family in a Siberian cellar in July 1918. The family had been into forced exile, imprisoned following Nicholas’ abdication for himself and Alexei in 1917 prior to the communist takeover.

The execution took place in a basement room in a Yekaterinburg mansion known as “The House of Special Purpose” — or the Ipatiev House.

The family was awakened that fateful night and led downstairs.

The assassins’ leader, Yakov Yurovsky, said the boy, 13, was shot repeatedly and bayoneted.

"Nothing seemed to work," Yurovsky is recorded as saying. "Though injured, he continued to live."

Like other family members, the boy wore clothes stuffed with precious stones. There were tales of gems causing bullets to ricochet around the small room.

Yurovsky said he shot the boy twice in the head.

Sandra said her husband told her of Yurovsky’s order to fire and that he remembered nothing after that. She said his ears were damaged by the gunfire and that her husband had a scar matching a bayonet wound.

Most of the family’s remains were dumped in a mine shaft. However, the vehicle moving the bodies got stuck on a muddy road.

To lighten the load, Alexei and Maria’s bodies were removed and carted off into the forest, doused with acid, burned and buried.

It was decades before those two bodies were found and DNA tests began to determine to whom the remains belonged.

Sandra says her husband remembered nothing until he awoke in the home of a family called Veerman, whose son had recently died. He took Ernest Veerman’s name. Soon, they had to leave the home.

While the trip from Yekaterinburg to St. Petersburg is currently 2,098 kilometres by train, that was not an option.

“They walked,” Sandra said.

Those moving through post-revolutionary Russia needed internal passports. They got them through performing plays about "the glories of communism," she said.

Arriving in Estonia in 1921, Sandra said her husband took the name Heino Tammet.

There, he worked as an editor. He also did caricatures bearing a remarkable stylistic resemblance to those done by the czarevitch, photos indicate.

The widow and her prince

In her north Burnaby living room, Sandra looks through family photo albums. She thinks fondly of her husband, who died 46 years ago.

The pair met on a White Rock beach and soon fell for each other. He said he was from Estonia and Russia before that. She was 16; he was 52 and running a ballroom dance school.

“He looked like 35,” she said.

They married July 23, 1960.

She was captivated by the man she called Aloysha, who had an aura of mystery.

Soon she asked who he was.

“He said. ‘The communists took over and they didn’t like us and they killed my family,’” Sandra recalled.

Once, while doing a foxtrot to a song called “Anastasia,” she noticed tears in his eyes. She asked why.

“He said, ‘I had a sister once. Her name was Anastasia.’”

Again, she asked who he was. He pointed her to a book called ‘Lost Splendor’ by Prince Felix Yusupov. At the library, she found a copy.

“I wasn’t looking for the czar of Russia,” she said. “I was looking for another little boy.”

“I am Alexei,” he told her.

Tammet-Romanov’s letter to prime minister

Prior to his death, Tammet-Romanov denounced pretenders claiming to be family members.

In a March 1971 letter to U.K. Prime Minister Edward Heath, obtained by Glacier Media from the U.K. Forensic Archive under freedom of information laws, he asked Heath to help stop “masquerading adventuresome people” from claiming “our family’s good name.”

He called them “despicable persons” “seeking money and fame.”

He enclosed photos of him he said were taken while he was in hiding with a family north of Yekaterinburg.

“Half a century I was quiet because I gave my oath to the people who saved my life, that murderous night that I would never tell anyone, anytime about my origin and my past,” he wrote, signing the letter Alexei Nicolaevich.

The DNA testing

In 1991, researchers identified sets of bones believed to the family’s. They used blood from Nicholas’ clothes and DNA from members of many European royal families, including many of Queen Victoria’s descendants, Prince Philip among them, to make the identifications.

The testing process went as far as exhuming Nicholas's father, Czar Alexander III, to prove "they are father and son," investigators said.

Evgeny Rogaev was on the team that did the DNA examinations.

“We have identified remains of Czarevich Alexey and published the data,” Rogaev told Glacier Media.

“Our genotyping data establish beyond reasonable doubt that the remains of the last Russian Emperor, Nicholas II Romanov, his wife Empress Alexandra, their four daughters (Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia), and their son (Crown Prince Alexei) have been identified,” the publication said. “Thus, none of the Nicholas II Romanov family members survived the massacre.”

Asked if there was any chance Tammet-Romanov’s claims were true, Rogaev said, “No chances.”

University of British Columbia history professor Alexei Kojevnikov isn't quite certain.

"Supposedly, his remains have been found but there is still some uncertainty about their scientific identification," he said.

"There were several dozen individuals who claimed the identity of Alexei Romanov after his execution," Kojevnikov told Glacier Media. "The Orthodox Church recognizes him as a martyr who was executed in July 1918 and thus rejects all the later pretenders."

However, he said, the church may need a miracle to be connected with the remains in order to confirm its belief.

"The final verdict of the official church has not yet been given," Kojevnikov said.

Pretenders to royal identities and associated conspiracy theories aren't unusual in Russian history, he added. Still, he said, they present an opportunity for people to learn about history.

"When the first original Russian dynasty expired around 1600, there was a teenager heir to the throne, who died in an accident," Kojevnikov said. "It was immediately accompanied by conspiracy theories that he was either assassinated... or survived the assassination attempt."

But, he added, "in the case of Alexei who died young, and also the case of some of his sisters, there were also for the several decades that happened since, there were a whole string of individuals who claim to be survivors."

Sandra sent documents and two of her husband’s teeth for DNA testing to U.K. forensic laboratories in 1993, leading to discussion among scientists Pavel Ivanov and Peter Gill.

“Although none of the above documents provide convincing evidence Mr. Romanov could really be the missing son or the Russian czar, it seems to me worthwhile to consider possibility to analyze his tooth specimen along with other selected pretenders,” Ivanov wrote to Gill in October 1993.

Two years later, Ivanov wrote to Sandra on U.S. Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory letterhead saying one of the two teeth had been destroyed as part of testing. He said he would keep the remaining tooth. Glacier Media obtained that letter via U.K. freedom of information law.

She never got the tooth back nor did she receive test results.

The RCMP arrive

Lord Louis Mountbatten was Prince Philip’s uncle and a friend of the late Marvin Lyons of Richmond, a Russian historian.

The Canadian Press spoke with Lyons about Tammet-Romanov in 2006.

Lyons had called police after Tammet-Romanov sent a letter of condolence to Queen Elizabeth II, signing it with the czarevitch’s title, after the Duke of Windsor — the abdicated Edward VIII — died in 1972.

Mountbatten had asked Lyons to look into Tammet-Romanov. After the letter to the queen, he called police. RCMP officers arrived at Tammet-Romanov's Burnaby home soon after.

Sandra said officials checked out her husband's claims, going as far as physical examinations of him for marks the heir would have sustained in the family’s killing.

Those marks existed, she said.

Tammet-Romanov showed them the scar from a bayonet in the execution. He also told them of an undescended testicle (which the czarevitch had), his widow explains.

She said investigators included members of the RCMP Security Service, now the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service or CSIS.

"There are all kinds of these people around," Lyons told the Canadian Press. "Most of them are not criminals. They're not even mentally ill in the normal sense of the word.

"They're just people who are unhappy about their role in life and are trying to create something that is more interesting.

"I've known about this man and his claims since the mid-1970s," Lyons said. "This is all make-believe."

But when Tammet-Romanov sent congratulations to Princess Anne and Capt. Mark Phillips on their Nov. 14, 1973 wedding, he received a response. It was addressed to Alexei Nicolaievich Czarevick, Grand Duke of Russia.

Glacier Media requested RCMP Security Service or CSIS files on the police investigation from Library and Archives Canada in 2018.

The bulk of information Glacier Media received was blanked out.

What was released related to Aleksandr Romanov, a Russian ‘diplomat’ stationed in Canada. Glacier Media made no request under that name.

‘The Russian Legitimist’ website is an unofficial examiner of the rightful heads of the Russian ruling dynasty. The editors told Glacier Media Tammet-Romanov was “a well-known Romanov impostor.”

“His claims were long debunked even before the discovery of the remains of Tsesarevich Alexis and his sister, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna in 2007 which proved the whole Imperial Family died at Ekaterinburg (Yekaterinburg).

“Heino Tammet was not a haemophiliac,” the editors said. “There is no question that the whole family was murdered at Ekaterinburg. This is something on which all sane people agree.”

A memorial website to the family notes more than 200 people claiming to be family members, several claiming to be Alexei. Heino Tammet is listed among the “most famous pretenders.”

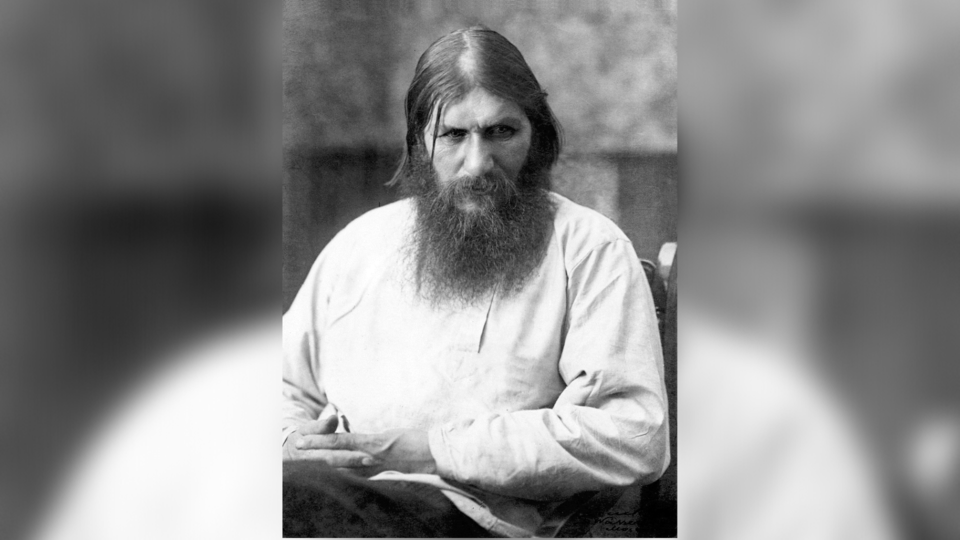

Haemophilia and the ‘Mad Monk’ Rasputin

Much of the tale of the last imperial family involves Alexei’s alleged haemophilia, a genetic disorder not unknown among Queen Victoria’s descendants, of which Alexei was one. Blood does not clot properly and can lead to spontaneous bleeding, especially following injuries or surgery.

The czarevich had bouts of bleeding often and frequently had to be carried by an attendant. The issue was one of great concerns to the family and not common knowledge outside royal circles.

History tells us the monk Rasputin appeared in St. Petersburg in 1905 and appeared to be able to alleviate Alexei’s suffering.

The family knew him as “our friend.”

However, those in royal circles and the government began to fear Rasputin had too great an influence on the czar and empress, and that he was dictating government policy.

In late December 1916, he was drugged and shot by noblemen, his body dumped in a river. He was buried at the Tsarskoye Selo palace but exhumed and burned after the revolution.

“Aloysha said he did have a power,” said Sandra. “I believe he had a hypnotic power. He said, ‘I do not care what the world says about Rasputin. He was my friend.’”

The Vancouver journalist

Vancouver journalist John Kendrick has long believed Tammet-Romanov’s claim, and has done significant research into the health of the czarevich. Much of it can be found on his website.

Kendrick believes Alexei was afflicted not with haemophilia but aplastic anemia or leukemia, which produces the same symptoms and can go into remission, recurring late in life.

Kendrick said “it returned to take (Tammet-Romanov’s) life in a Vancouver-area hospital bed on the 26th of June 1977.” Sandra told Glacier Media her husband died of myeloid leukemia.

Kendrick’s work on the subject was published in the American Journal of Hematology in 2004.

There, he said writing by those at court, notably Nicholas and tutor Pierre Gilliard, described symptoms akin to hemolytic anemia.

“It is entirely possible that the only son of Russia’s last Tsar Nicholas II was not a hemophiliac, as is popularly believed. The symptoms of a blood disorder recorded in the case of the young Tsarevich Alexei are a much better match with the classic description of episodes of crisis in hemolytic anemia,’ Kendrick wrote.

But what of the escape?

Kendrick believes that has something to do with the wishes of German Kaiser Wilhelm II and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that ended Russia’s participation in the First World War.

He speculates that Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin owed the Germans a favour, resulting in the kaiser's Field Marshall Paul von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg being asked for help by the czar's Grand Marshall Count Paul Benckendorff.

Kendrick said after the execution, the czarevich was placed in the care of another member of the Benckendorff family (the Veermans) and was taken out of Russia to Estonia one full year after the armistice that ended Russia's revolution.

“The two shots that execution squad commander Yakov Yurovsky had fired at the Prince's right ear twenty-six days before his fourteenth birthday were blanks,” Kendrick wrote.

twitter.com/jhainswo

Story written by Jeremy Hainsworth, video produced by Alanna Kelly.