About a two-hour drive south of the Canada-U.S. border, the lands of the Flathead Indian Reservation rise out of Montana’s western sierra, just north of Missoula.

Nearly 170 years ago, when the reservation formed under the Treaty of Hellgate, the Salish and Kootenai tribes were promised rights to hunt and fish off reservation in their traditional territory. Over the years, that has sometimes led to violent confrontations.

Today, many of the 7,800 members who make up the tribal federation have been scared off by something more insidious — compounds invisible to the eye but growing in concentration as Canada’s largest grouping of coal mines pumps pollutants downstream, says Tom McDonald, chairman of the Coast Salish Kootenai Tribes of Montana.

“Mining has a serious impact severing us from that landscape,” said McDonald from his home on the reserve. “We don't feel comfortable eating the fish there anymore when the fish are missing part of their gill plate. That shakes you up quite a bit.”

“It’s like you’re eating a fish with cancer. It’s just a horrible thing.”

Besides deformed cutthroat trout, McDonald said his people have seen a “dramatic decline” in the reproductive capability of burbot, a freshwater cod historically important to local Indigenous people.

“They're not trying to spawn,” he said. “It’s another side effect of too much selenium in this system.”

A trace element for life

Selenium is a trace element for life. But too much is toxic and can be especially damaging for egg-laying creatures, such as fish and birds. By filling the role of sulphur in proteins, selenium is known to trigger deformities, though its spectrum of effects is not clear, say biologists.

“These are contaminants that build up and don't go away,” McDonald said. “What's it doing to the mallard ducks? What is it doing to the trumpeter swan? What is it doing to the white-tailed deer? Or, what's it doing to the humans?” he questioned.

Along with nitrate and sulphate, selenium levels have exceeded Canadian water standards in B.C.’s Elk Valley on multiple occasions. Between 2015 and 2022, 55 inspections led the B.C. government to issue 19 warnings and 13 referrals for administrative penalties, including a nearly $16-million fine issued to owner Teck Resources Inc. earlier this year.

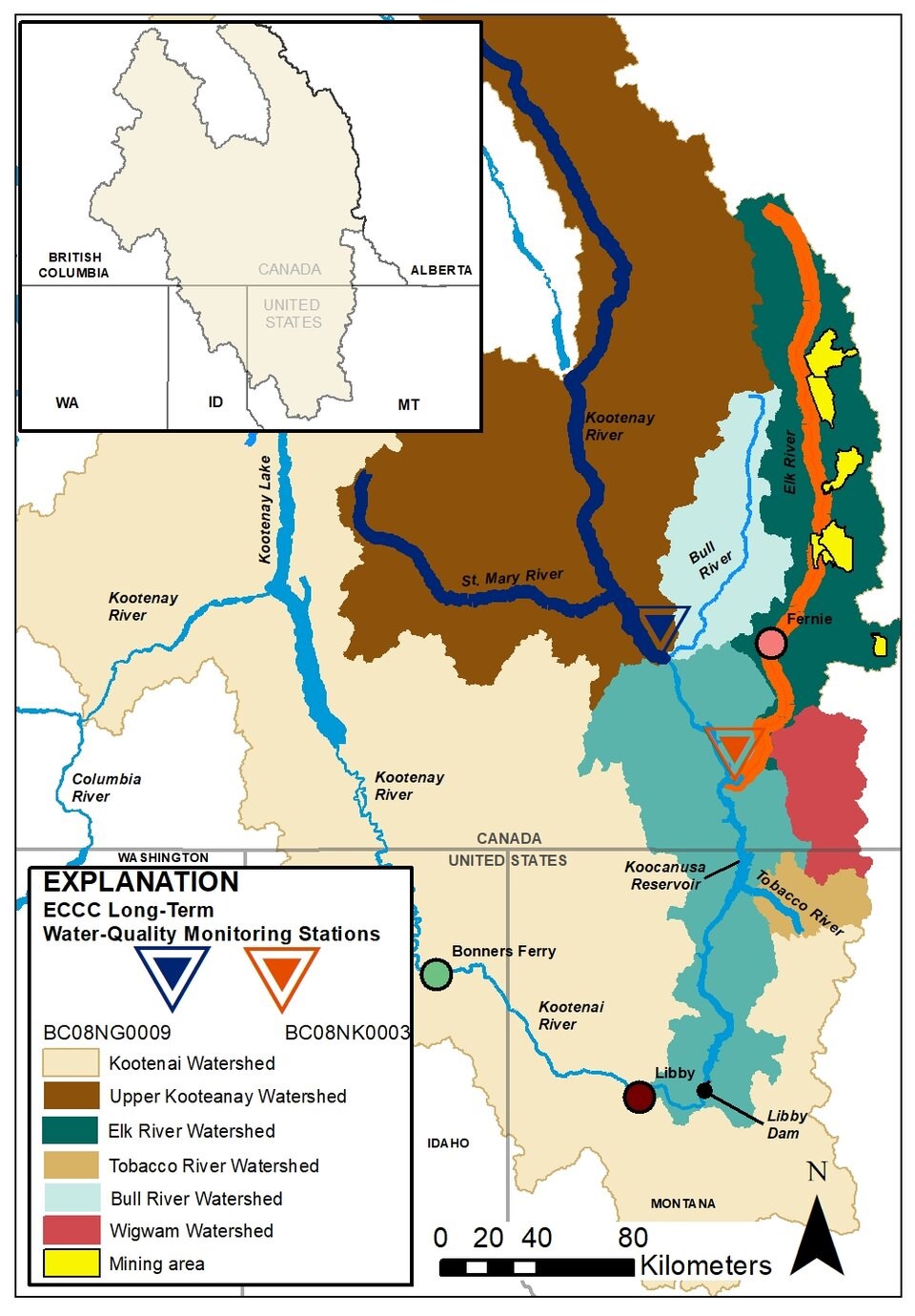

Other third-party studies have raised questions about the impact of coal dust on the nearby communities. But until recently, no comprehensive study has tracked water pollution past the last mine, as the river meanders 80 kilometres south into Montana, where it empties into the Koocanusa Reservoir.

This month, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) released a study showing the Kootenai watershed had seen an unprecedented increase in selenium.

Mine runoff makes up only three per cent of the Elk Valley watershed, but when the researchers compared the water’s chemistry with the nearby Kootenay River, where the effects of coal mining are absent, they found vast differences in selenium, nitrate and sulphate levels going back to the mid-1980s when records began.

The landmark study, published in the journal ACS Publications, found the multi-decade per cent changes of selenium in the Elk River were the largest ever recorded in a peer-reviewed study — anywhere. By the end of 2022, selenium concentrations jumped 551 per cent, nitrates climbed 784 per cent, and the concentration of sulphates spiked 120 per cent.

Meryl Storb, a hydrologist with the USGS and the first author on the study, said while the numbers provide “strong evidence” of contamination from the mines.

“I mean, these are among the largest per cent changes that we know about,” Storb said. “We couldn't find anything larger.”

High selenium levels prompt U.S. senator to call for escalation

Teck's treatments to reduce downstream selenium concentrations have had some impact in the fall and winter, when low water levels and high selenium concentrations means its four treatment plants have the biggest effect, the study found. But overall, those reductions haven’t done much to change the overall mass of contaminants going downstream every year — something that has been “pretty consistent over time,” said Storb.

“Since the year 2000, measured selenium concentrations have consistently exceeded the recommended ambient water quality guidelines,” she said.

Selenium concentrations weren't researchers' only focus. Throw off the nitrate balance, explained Storb, and you can change the composition of algae. That can alter the base of the aquatic food web, and later ripple up the prey chain to bugs, bug-eating fish, and beyond.

McDonald said the study is just one more “red flag” that confirmed what many in his nation already knew.

“We've been working at this, trying to really scream out that there's an issue here, since well, 10 years,” he said.

Last week, that fight was brought to the U.S. government's top diplomat. In a letter dated Nov. 14, Montana Sen. Jon Tester (Dem.) called on Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to refer the ongoing pollution of the Kootenai watershed to the International Joint Commission, a bi-national organization set up in 1909 to resolve disputes surrounding shared waterways along the Canada-U.S. border.

Tester urged Blinken to “work with Canada” but advance unilaterally “if Canada remains unwilling to meaningfully engage on this issue.”

“The selenium contamination issues only continue to compound in northwest Montana, and we can no longer delay a solution,” wrote the senator.

Tester wasn’t available for an interview by publication time.

B.C. government, Teck disagree with study

In an unattributed statement, the B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy said the conclusions “do not fully align with the ministry’s knowledge and understanding of the Elk Valley.”

The spokesperson said the USGS study incorrectly states there is a lack of understanding on what’s driving water quality changes and whether planned water treatment is sufficient. The statement said it was incorrect to conclude there were knowledge gaps when it came to what’s happening with groundwater.

The province said it is looking for a facilitator to finalize the selenium water quality objective for B.C.'s portion of the Koocanusa reservoir and backs a March 2023 commitment made between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and U.S. President Joe Biden to reach an “agreement in principle” to reduce and mitigate the impacts of water pollution on the watersheds.

A statement from Teck, meanwhile, said the company is making “significant progress implementing the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan” and that its water treatment plants remove between 95 and 99 per cent of selenium from treated water. A spokesperson said selenium concentrations have “stabilized” and are dropping downstream of treatment.

“We have constructed four water treatment facilities to date treating 77.5 million litres of water per day and we expect to further increase our water treatment capacity by 2027 to 150 million litres per day,” read an email statement attributed to the company.

The spokesperson pointed to a Teck “factsheet” indicating U.S. water quality shows selenium concentrations “for all fish in the Kootenai River and Koocanusa reservoir, on both sides of the border, are well below US EPA protective criteria.”

The company did not directly address the USGS findings that total annual load of selenium has changed little in recent years.

Teck prepares to sell off coal business

Last week, Teck announced it was moving forward with the sale of a majority stake in its Elk Valley coal mines to the Anglo-Swiss mining company Glencore. The deal, valued at US$9 billion, is expected to close in the third quarter of 2024.

When asked about how Teck would ensure its operations in Elk Valley don’t continue to pollute waters downstream of the mines, a company spokesperson pointed to “numerous commitments” Glencore has made to protecting the environment and water quality. Those included, continuing the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, increasing its Canadian research and development budget for water quality treatment technologies by 50 per cent over current levels.

But McDonald said he would rather see that work carried out at the International Joint Commission, where B.C. says it has proposed it play a “neutral third-party” role, and where independent bodies on both sides of the border can carry out independent science to give his tribal federation a fuller picture of the damage selenium is doing.

“They've been allowed to continue to pollute and even increase the pollution level. And now they're selling it. And, man, it's just like, one insult after another,” said McDonald. “How can you continue to allow them to operate when they're violating the law?”

“Why bother have any law at all?”