When a patient in her 70s came into the emergency department at Kootenay Lake Hospital in Nelson, B.C., Dr. Kyle Merritt had no idea hundreds of people were dying of heat across the province.

It was late June, and British Columbia was consumed under a heat wave that would soon go down as both the hottest and deadliest in Canadian history.

The head of the hospital’s emergency department, Merritt could see the aggravated toll the extreme heat took on patients battling multiple health problems at once, often with little money.

“She has diabetes. She has some heart failure. … She lives in a trailer, no air conditioning,” says Merritt of the senior patient.

“All of her health problems have all been worsened. And she's really struggling to stay hydrated.”

As the mercury climbed, more patients arrived and pressure on the hospital mounted. Merritt and his colleagues tried to make sense of a surge in heat illness most had only seen in medical school.

“We were having to figure out how do we cool someone in the emergency department,” says the doctor. “People are running out to the Dollar Store to buy spray bottles.”

Merritt remembers hitting a tipping point, the extreme heat an opening salvo in another summer of crisis. He started contacting other doctors and nurses, in Prince George, Kamloops, Vancouver and Victoria.

The response was immediate. Roughly 40 doctors and nurses at the small hospital — all busy trying to manage a pandemic and their regular professional lives — came together under the banner Doctors and Nurses for Planetary Health.

“I was worried about the summer that was coming,” says Merritt of the rising number of health-care workers desperate to talk about how climate change is affecting their patients’ health.

“I was really quite amazed at how many people have decided to jump in.”

Just as doctors and nurses started to make sense of the record heat, it cleared — only to be replaced by a blanket of wildfire smoke.

Climate change enters the ER

Like so many summers in recent memory, this summer, Nelson’s air turned the colour of pea soup, leading to a spike in patients suffering respiratory problems.

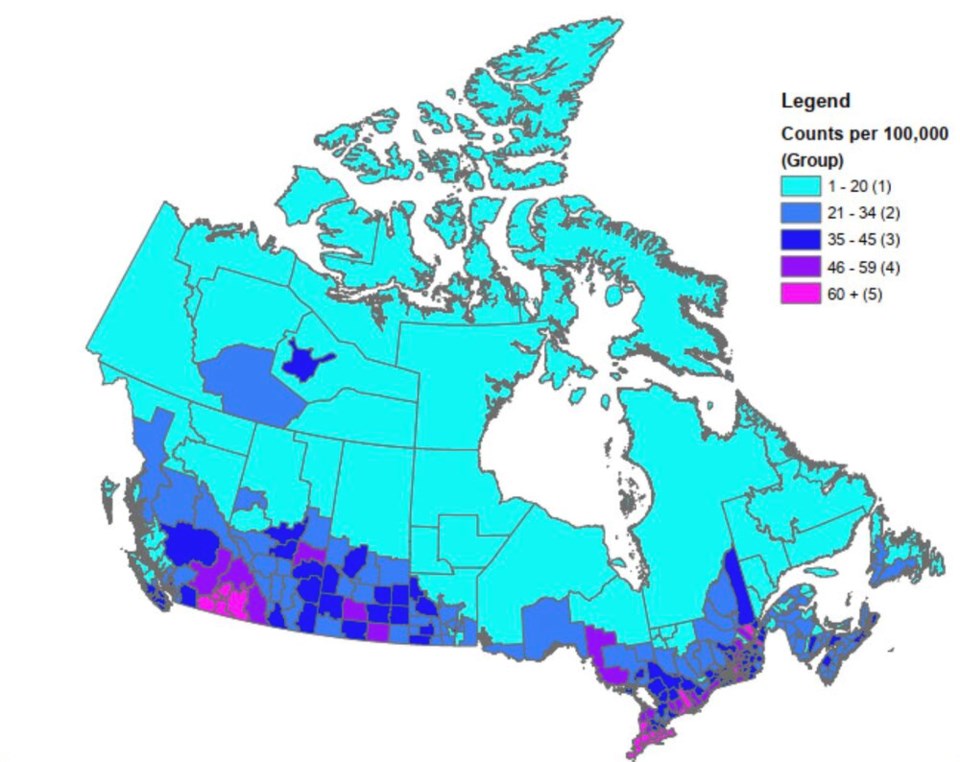

B.C.’s Interior suffers some of the greatest fallout from air pollution in the country.

Between 2013 and 2018, the 10 census divisions in the country with the greatest exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) were all in B.C.’s Interior, according to a 2021 Health Canada analysis of the impacts of air pollution on human health.

Of those, half the census divisions — including Central Kootenay, where Nelson is located — were among the top 10 slices of the country with the highest per capita rates of premature death.

“A lot of people in the Kootenays sort of thought that this would be a good place to hide out while the rest of the world falls apart. But it's, of course, hitting us here, just like it's hitting many places, and we're really seeing the impacts,” says Merritt.

Like death by heat, doctors have traditionally struggled to clinically attribute mortality and severe illness to air pollution. For Merritt, this summer’s wildfire season changed all that.

When a patient came in struggling to breathe, Merritt knew the smoke — that hadn’t lifted from the region for days on end — had made a case of asthma worse.

For the first time in his 10 years as a physician, the ER doctor picked up his patient’s chart and penned in the words “climate change.”

“If we're not looking at the underlying cause, and we're just treating the symptoms, we're just gonna keep falling further and further behind,” he told Glacier Media when asked why he did it.

“It's me trying to just ... process what I'm seeing. We're in the emergency department, we look after everybody, from the most privileged to the most vulnerable, from cradle to grave, we see everybody. And it's hard to see people, especially the most vulnerable people in our society, being affected. It's frustrating.”

At the same time, Merritt says he hoped another family physician would read the chart, and one day, consider drawing a straighter line between their patients’ health and climate change.

Smoke and heat affect more than peoples’ physical health. Merritt says he saw a number of patients already suffering from depression or anxiety have their symptoms worsen during the wildfire season. Wildfire smoke even triggered flashbacks in a patient who was coping with post-traumatic stress disorder from his time as a soldier.

As the medical community learns more about the devastating impacts of smoke and heat, even people who don’t suffer from pre-existing health conditions are facing tough decisions, including doctors like Merritt.

“This past summer, it was so bad for about three weeks,” says Merritt.

“What do you do with your children? You know, I have three kids, and they're inside, it's summertime, we've just got through COVID. And they want to go out and jump on the trampoline. So I have to try and figure out: Is that safe?”

Doctors at the feet of power

As global heating takes centre stage in Glasgow this week, Merritt and about 40 other nurses and doctors are taking their concerns to Nelson’s city hall, where the group will rally alongside at least 130 more health-care workers demonstrating at the provincial legislature in Victoria.

“We wanted to do something big. We wanted to gather at the feet of power,” says Dr. Kelly Lau, a family physician based in Vancouver, who is among those headed to Victoria Nov. 4.

Starting Thursday at noon, Lau says the non-partisan group is calling on the provincial government to, among other things, declare an “ecological emergency” and end subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.

“A lot of us were really shook by this summer, by the heat dome and the wildfires that are just escalating every year,” she says. “This is about moving forward in a way that saves lives.”