An environmental group is taking the federal government to court over what it says is a failure to enact a protection order meant to safeguard habitat for the last northern spotted owl still living in the wild.

In February, Canada's Minister of Environment Steven Guilbeault said he would issue an emergency order to protect 2,500 hectares critical spotted howl habitat his ministry deemed at risk from logging in B.C.’s Fraser Canyon.

“Notwithstanding these findings, the minister has failed to make an emergency order recommendation to cabinet, as he is required to by law. Nor has he committed to any timeline for doing so,” the law firm Ecojustice said in a statement.

Lawyers from the firm filed an application for judicial review on behalf of the Western Canada Wilderness Committee at a Vancouver federal court on Wednesday. The court action asks the judge to declare the delay “unlawful” and to compel the minister to follow through on his obligations under the Species at Risk Act within 15 days of the court's judgment.

In an email, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change said it's working with the B.C. government to back the spotted owl breeding and reintroduction program, control invasive species and protect habitat.

“Following appropriate consultations with First Nations and the government of British Columbia, the Minister will make a recommendation to the Governor Council for measures to protect Spotted Owl from imminent threats to its recovery,” wrote spokesperson Brandon Clim.

Clim declined to comment on the court challenge.

Recovery efforts face setbacks after two deaths

The B.C. government recently extended a halt on logging in Spuzzum and Utzlius creek areas until early 2025 — two watersheds where the last wild-born owl now lives.

Recovery of the spotted owl has faced significant setbacks in recent months. In May, two owls bred in captivity and released into the Fraser canyon watersheds were found dead.

It’s not clear what killed them, though Spô'zêm First Nation Chief Joe Hobart said they were found outside of their designated habitat and suspects they succumbed to starvation.

“The two owls flew out of the protected area,” Hobart said.

“So the government is saying one thing about what they're doing to protect the spotted owl, but the spotted owls aren't reading those maps, they're flying right out of that area.”

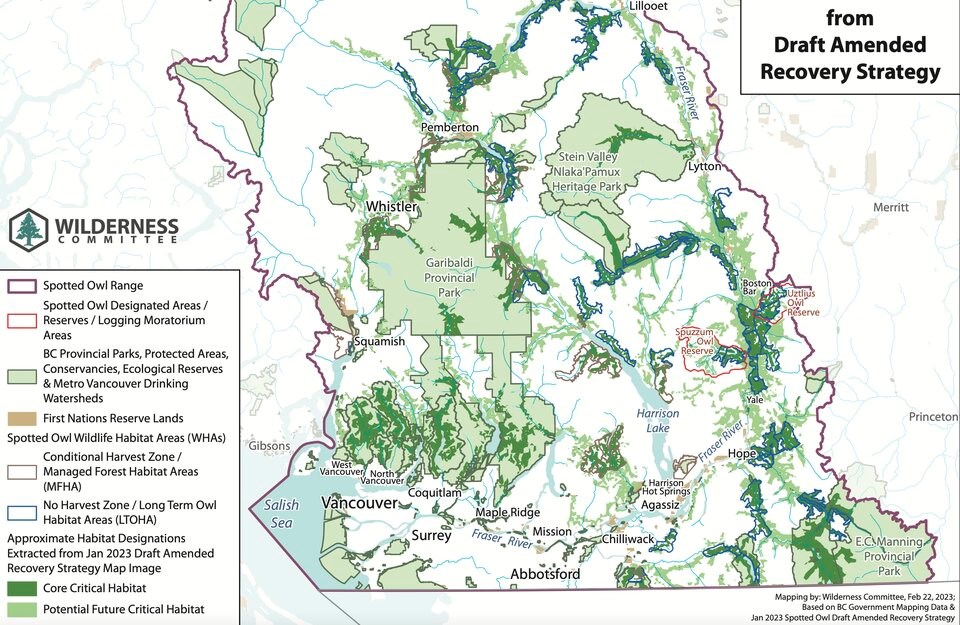

Scientists estimate there were once 500 pairs of spotted owls living in southwest British Columbia’s old-growth forests. Core critical habitat for the northern spotted owl stretches from the Lower Mainland, through the Squamish Valley to Whistler, Pemberton, down the Fraser Canyon and south into Manning Park.

As those forests have shrunk or been degraded, so too has their range. Competition from other invasive owls, like the barred owl, has added to the spotted owl's struggle to survive, said Hobart.

Today, a single wild-born owl occupies two patches of forest near Spuzzum and Utzlius creeks in the Fraser Canyon.

Fraser canyon logging threatens critical spotted owl habitat

The status of the species prompted the federal government to release a draft recovery plan for the spotted owl earlier this year. Among other things, the plan presents a series of maps outlining what forests need to be protected in order to save the species in Canada. But logging outside of the protected areas continues, the Wilderness Committee says.

Joe Foy, the Wilderness Committee's protected areas campaigner, said his group took those federal maps and then overlaid them with provincial maps showing pending and approved forest cut blocks in B.C. When Foy and some of his colleagues visited the Fraser Canyon forest sites at the end of last month, he said they found logging had already started in places where critical spotted owl habitat was meant to be protected.

“Logging is nailing these areas under permit from the province of B.C.,” he said. “It freaked us out. It goes against what the federal government has been telling us since February.

“These really important areas are being hauled down the road on logging trucks. That’s why we’re going to court.”

Editor's Note: This story has been updated with a response from the Government of Canada.