Six Canadian provinces and one territory saw December temperatures spike to their warmest levels since 1970 in a trend strongly driven by climate change.

On average, temperatures across Canada spiked more than five degrees Celsius above average in the last month of 2023, according to an analysis from the U.S.-based research group Climate Central.

“To have a whole country-wide temperature anomaly that pushes you over that edge… that's unusual,” said Andrew Pershing, Climate Central’s vice-president for science.

“Those are the sorts of events that really make you think climate change.”

Climate change’s fingerprint was felt strongest in Canada’s territories as well as British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and New Brunswick, said Pershing, who led the study.

In Nunavut and Northwest Territories, warmer temperatures were made at least twice as likely for almost half of December. Among Canada's provinces, B.C. and Ontario recorded the strongest influence from climate change, with warmer temperatures made twice as likely more than a third of the month.

And for more than a week, December temperatures in B.C. were made at least three times more likely due to climate change. That's more than any other Canadian jurisdiction.

Canada a harbinger of global warming

The analysis comes after verification of what was long expected to be the hottest year ever recorded on planet Earth.

On Friday, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced the 10 warmest years in its climate record have all occurred in the past decade.

“Not only was 2023 the warmest year in NOAA’s 174-year climate record — it was the warmest by far,” NOAA chief scientist Sarah Kapnick said in a release.

Pershing said Canada was “very much” part of that pattern, one that saw global temperatures “jump up” in the latter half of the year.

“It's climate change. It's absolutely human-caused climate change,” he said in an interview Monday. “This is a year where we should be setting records, where we basically have warmed up enough to equal what El Niño was adding in 2016.”

It's official—2023 was the world’s warmest year in @NOAA’s 1850-2023 climate record. The 10 warmest years since 1850 have all occurred in the past decade. More from the 2023 global #climate report: https://t.co/x9YhCuQQIo #StateofClimate pic.twitter.com/lm1FFeJRAl

— NOAA Satellites - Public Affairs (@NOAASatellitePA) January 12, 2024

At a local level, several B.C. communities broke all-time mean temperature records for December.

In the Victoria Harbour area (Victoria Gonzales CS), mean temperatures climbed 2.5 C above normal in the warmest December since 1874.

Williams Lake saw temperatures spike 6.9 C above December’s mean, the warmest since records began in 1961. And at Vancouver International Airport, a 3.4 C mean temperature anomaly beat any December temperature going back to 1896.

While El Niño’s impact is forecast to grow in the early months of 2024, Pershing said it had little effect on the overall rise in global temperatures in 2023.

“There's clearly some weird stuff going on, but at the end of the day, it really is climate change,” said the scientist.

Drought could ‘spell disaster’ for B.C. wildlife, warns group

B.C.'s warmer temperatures have come amid persistent dry conditions across much of the country.

Last week, Watershed Watch Salmon Society warned that record-low snowpack could “spell disaster” for B.C. this summer.

While snow has begun falling in some areas, there remains a big snowfall deficit. Watershed Watch executive director Aaron Hill said he is worried there won't enough water in the province's rivers as young salmon migrate to the sea in the spring and the adults return to spawn in the summer and fall.

“With the snowpack and these warm conditions we had in December, I’m worried things will be as bad or worse in the spring [and] through to the fall,” Hill said.

Hill and his group are calling on the B.C. government to prepare communities for a difficult drought season ahead. Among its recommendations, Watershed Watch said B.C. needs to provide at least a billion dollars to fund long-term drought prevention projects that would allow First Nations and local communities to prepare for worst-case scenarios.

“That can alleviate some of the conflict when people have their water shut off,” he said.

‘Dice are loaded’ for another destructive wildfire season

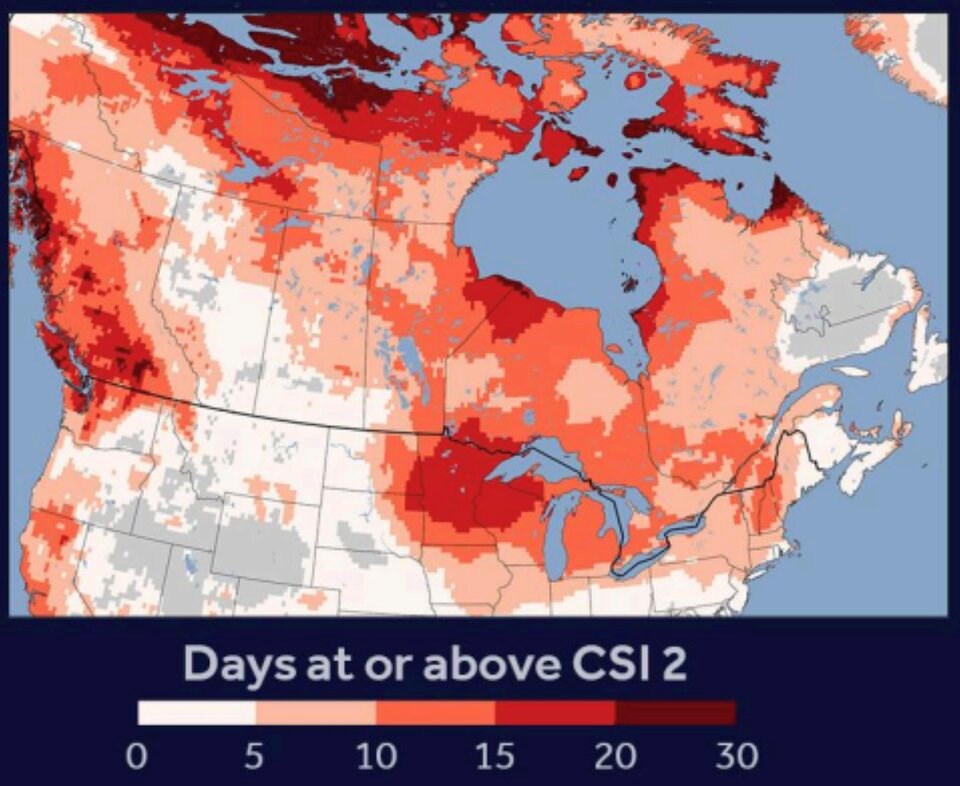

Canada’s 2023 wildfire season was by far the most destructive on record, and some experts worry ongoing drought could lead to a repeat this year.

As of Jan. 15, BC Wildfire Service data showed at least 105 wildfires burning across the province. The so-called “zombie fires” are not uncommon, but that many fires still burning at this time of year worries Mike Flannigan, a professor at Thompson Rivers University researching fire weather and climate change.

“That’s a lot of fires,” he said. “You get some warm, dry weather and those fires can grow again.”

Environment Canada's long-range forecasts show above average temperatures over the coming months. Flannigan said persistent drought conditions layered on top of that mean “the dice are loaded for a very active spring” — especially in northeast B.C., northern Alberta, and the Northwest Territories.

It’s all part of a larger global forecast Pershing said will bring more extremes — sometimes persistent drought, other times a burst of extreme rain or snow.

“It's just really hard to imagine the 2024 won't set a global record,” he said.

How that will translate into wildfires will depend on B.C.’s June rains and the day-to-day weather during the fire season, Flannigan added.

Whatever happens, B.C. is among the regions that will continue to feel the impacts of climate-driven wildfires first.

“We're the sharp point of the spear,” said Flannigan.