James Allan never gave up on the idea that he might one day be reunited with his older brother.

William Allen (the two spelled their name differently) had disappeared from his life when the two were young children.

Their parents had emigrated from Scotland, but their mother was institutionalized. Their father was unable to cope with raising two children, so he sent William, who was about four years older, to the B.C. Protestant Orphans’ Home — the predecessor of today’s Cridge Centre for the Family.

James was handed over to the care of two women who lived in Victoria.

“Dad told me that he tried to find out about his brother from the orphanage when he was in his late teens, but couldn’t find any information on him,” said James’ daughter, Langford’s Tanna Allan, 59.

What her father didn’t know was that his brother was likely living at that time in Nelson, where he worked as a cook before he enlisted in 1940.

Later in life, James, who died in 2002, even bought a home across from the house on Craigflower Road where the two were both born in hopes that should his brother one day return to his birthplace, he would see him, said his daughter.

It wasn’t to be.

Pte. William Allen, who served with the Westminster Regiment (Motors), was killed in action Nov. 18, 1944, in the Italian province of Ravenna, which saw fierce fighting by Canadian divisions from the British Eighth Army.

He is buried with fellow Canadians at the Ravenna War Cemetery, near the village of Piangipane.

Tanna Allan only recently discovered her uncle’s fate, when she learned that he will be remembered in a ceremony at his graveside in Italy this month, on the anniversary of his death — courtesy of an Italian organization that works to keep alive the memory of soldiers killed in the liberation of that country.

In honour of the 956 soldiers killed in the liberation of Italy, an Italian group called Wartime Friends holds such graveside ceremonies on the anniversaries of their deaths. They try to locate family members, then record the ceremony and share it with the family.

When the organization tracked down Tanna Allan, it discovered that William Allen had been orphaned at an early age and considered the orphanage his family.

In his will, in fact, Allen left all his “worldly possessions, what savings I may have and my army wages due of $1.10 per day” to the B.C. Protestant Orphans’ Home, which he called the “only home I’ve ever known.”

The 100-bed B.C. Protestant Orphans’ Home operated from 1873 to the early 1970s, and became the Cridge Centre for the Family in the early 1980s.

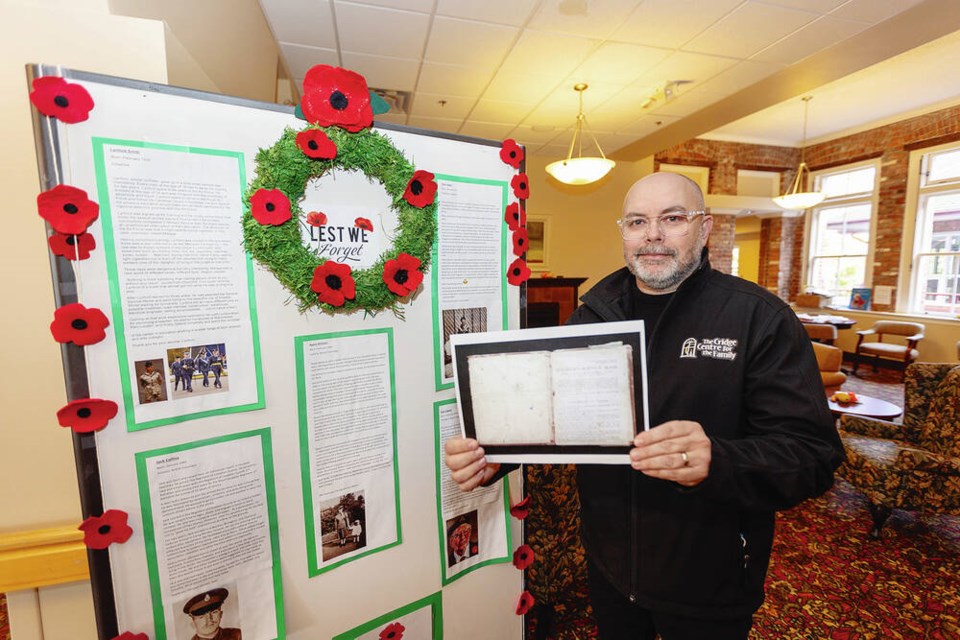

Adam Richards, the centre’s CEO, said the home cared for about 1,600 children over the years.

The orphanage received about $1,900 from Allen’s estate, as well as his campaign medals, which were sent there in 1949, although their current whereabouts are unknown.

For Tanna Allan, the “out of the blue” call from Wartime Friends was bittersweet — it finally provided answers about what had happened to her uncle, although it wasn’t the ending she was hoping for to the 30-year search.

Allan said she appreciates the efforts of Wartime Friends in recognizing her uncle’s life and reaching out to her.

While she can’t be at the ceremony to honour him, she said she hopes to visit his grave in Italy one day.

“While my dad and I always observed Remembrance Day over the years, this makes it that much more personal.”