Less than a week after B.C. was hit with mass flooding and devastating landslides, a group of scientists quietly testing a new atmospheric river warning system are accelerating its launch and say it could be ready within months.

“In some respects, it was the perfect storm,” says Matthias Jakob, a UBC adjunct professor in the earth and ocean science department, and one of the researchers on the project.

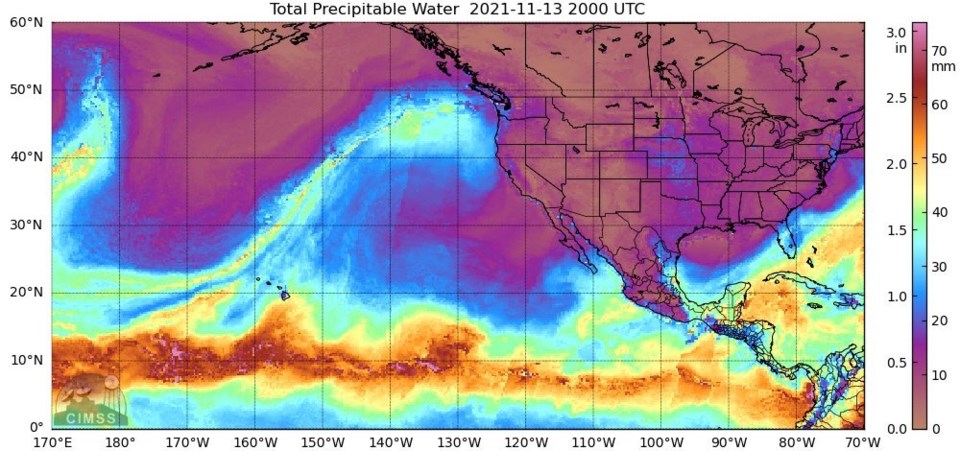

Atmospheric rivers are not an unusual phenomenon. Throughout the winter, the long ribbons of water vapour regularly funnel warm, subtropical air from lower latitudes to B.C.'s coast. Moving with the weather, atmospheric rivers stretch thousands of kilometres and carry moisture “equivalent to the average flow of water at the mouth of the Mississippi River," according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

What was different this time around, says Jakob, was its duration and intensity — over the space of 48 hours, at least 20 rainfall records fell across B.C.

At least 17,000 people have been displaced by the flooding, and hundreds more have been trapped or cut off, and in some cases killed, after debris torrents wiped out highways. But the province, and indeed Canada, has no ranking system to put such powerful atmospheric rivers into context.

It's part of the reason Jakob says he teamed up with Environment Canada about a year and a half ago to find a solution.

Ranking catastrophic weather events has historically been reserved for the most spectacular events. Communities about to get hit by a hurricane get a 1 to 5 warning based on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale. Those in tornado alley (or even Vancouver) can gauge the intensity of an incoming twister through the Enhanced Fujita scale, which ranges from EF0 to EF5.

What was missing for Canada, concluded Jakob and his Environment Canada colleagues, was a scale to classify atmospheric rivers, or what meteorologists call extra-tropical cyclones.

“We started to develop a categorization system that not only determines how much moisture gets put into our region, but also the precipitation, the return period, the runoff — it’s really multi-variate,” says Jakob.

A WARNING SYSTEM BASED ON IMPACT

California researchers have already developed a rating system for atmospheric rivers, which shows the change in atmospheric moisture over time. That system ranges from AR CAT 1 (primarily beneficial) to AR CAT 5 (primarily destructive). The Canadian scale is looking to build on that, adding the consequences of everything from nuisance flooding to catastrophic flooding affecting half the province.

“Our scale is based on what is the impact, not just the strength of the atmospheric river," says Ruping Mo, a senior research meteorologist with Environment Canada based in Vancouver and one of 10 people developing the rating system.

The system starts at AR1. That’s where TV networks and the press might start warning drivers to be careful of puddles on roads. At AR5, highly destructive “superstorms” would create havoc over a very large area.

Whatever the intensity of an incoming atmospheric river, the idea is to give meteorologists — and through them, the public — useful information to manage personal risk.

How would this system classify the storm that just hit B.C.?

Mo says his team has been quietly running the atmospheric river ranking model internally to see how it works. When they tested it on last weekend's devastating storm 10 days before it hit the coast, it came back as an AR4. By Saturday, Mo says they bumped it up to an AR5.

“We’ve never seen an event like that,” he says. “This event really caught us by surprise. We didn’t expect the impact would be so huge.”

Still in the experimental stage, Mo says he needs to work out what went wrong and how to fix it before Environment Canada releases it to the public sometime between December 2021 and January 2022.

“We still have something we don’t understand. There are some lessons we need to learn,” he says.

SHIFTING LOCAL BASELINES

Mo says the atmospheric river scale uses historical rainfall data from across the province to tailor warnings to different communities. For example, the same storm might trigger an AR3 warning in a coastal rainforest that can handle a lot of rain and an AR4 in a relatively dry Interior forest.

“If 100 millimetres fall on the west coast of Vancouver Island in 24 hours, that’s normal,” he says. “But for Hope or Abbotsford, that’s a lot of precipitation.”

One challenge confronting Mo and his team: historical baselines are quickly shifting as climate change warps what forecasters once considered normal precipitation.

Still, after this week, Mo says his team is working hard to make the atmospheric river ranking system public before another weather event hits.

Though rare now, the largest atmospheric river events are expected to become more frequent and intense in the future.

At the high end, Jakob says the province could see 500 millimetres over 48 hours, more than double the rainfall that has paralyzed B.C. this week.

“Atmospherically, it’s possible. It’s not out of the question,” says Jakob. “The sky's the limit for one of these superstorms.”