A Canadian police unit and security company aggressively surveilled, intimidated, beat and arbitrarily arrested members of the Wet’suwet’en Nation and their supporters while they defended their land from the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline, a new report from Amnesty International says.

The report, released early Monday, is based on witness testimony from four “large-scale raids” carried out by the Royal Canadian Mountain Police's Community Industry Response Group (RCMP-CIRG) on Wet’suwet’en territory between 2019 and 2021. It found the detachment's tactics in those “militarized” operations were “disproportionate” to the situation and were part of a pattern of human rights violations.

Wet’suwet’en hereditary Dinï ze’ (Chief) Woos, Frank Alec, said the report raises questions over Canada’s place in the world as a leader on human rights.

“This is supposed to be a free country. This is supposed to be Canada, the United Nations’s poster boy or something,” said Chief Woos.

“But look what’s happening in our backyard. It was hard to watch.”

When Amnesty International researcher Mary Kapron visited Wet’suwet’en territory to investigate the chain of events, she said police constantly followed her team. She found her experience there was just a glimpse of a pattern of “extremely excessive” surveillance, daily intimidation and harassment that violates rights to security of the person, personal integrity and privacy.

“They're trying to go berry picking and they’re followed,” said Kapron of Wet’suwet’en people. “That feeling of unsafety is a violation of their rights, to be able to live a life with dignity and fully enjoy their territory as Indigenous peoples.”

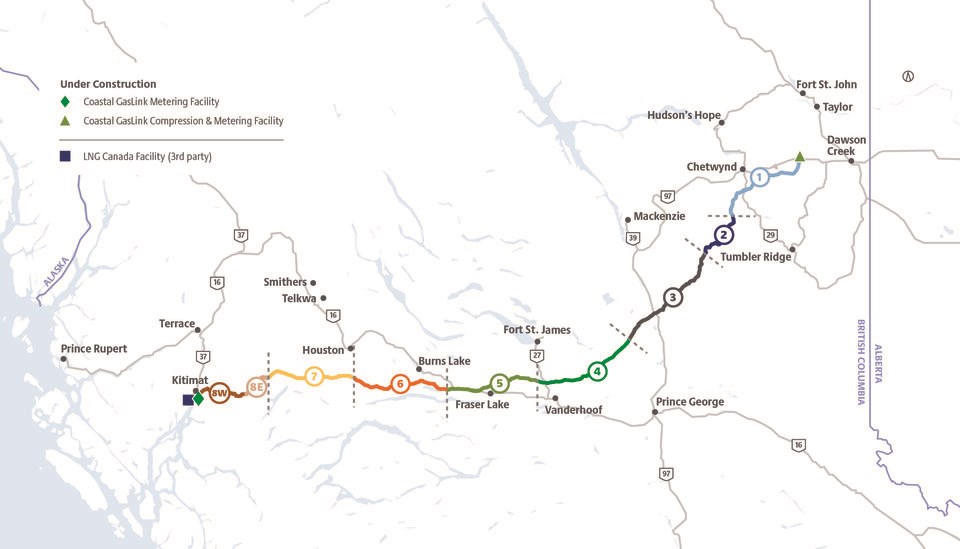

Passing through traditional Wet’suwet’en territory, the $14.5-billion Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipeline is the largest project of its kind in Canada. The recently completed pipeline spans 670 kilometres, connecting gas fields in northeast B.C. with a massive processing facility, known as LNG Canada, on the coast. Once operational, the fuel, largely methane, will be super-cooled into a liquid and loaded onto ships for export.

Of the 20 elected Indigenous band councils who formally support the pipeline’s construction, 17 First Nations along the route of the pipeline have community benefit agreements with CGL.

But pipeline opponents within the Wet’suwet’en have never supported the project and have repeatedly attempted to halt work through road and bridge blockades.

Opposition to the project has gained momentum among climate activists as well. Critics say the pipeline and liquefied gas terminal in Kitimat will make it impossible for B.C. to reach its emission reduction targets.

The B.C. government, however, maintains the massive gas project is tailored for a world shifting toward renewable energy, where it says global markets are expected to favour “lower-carbon natural gas producers.”

'I feel less safe now'

In one case detailed in the Amnesty report, 50 armed officers, helicopters and surveillance drones moved in to arrest 15 people peacefully protesting near the Morice River (Wedzin Kwa). In other raids, Amnesty says Indigenous people had their hair pulled, and were kicked and punched in the head after dozens of police officers moved in, armed with semi-automatic sniper rifles, dogs, bulldozers and helicopters.

Amnesty says it also documented a pattern of “unlawful surveillance,” intimidation and criminalization, which in one instance interrupted a ceremony to mourn the death of an Indigenous community member.

The report alleges Wet’suwet’en land defenders faced racial discrimination and “threats and acts of gender-based violence” from pipeline workers or members of the security company. Kapron said in one interview a Wet’suwet’en woman described how she was travelling down a single-lane forest service road when the radio came to life. On the other end, a man threatened to rape her.

“I feel less safe now that [my daughter] plays outside knowing there’s a strange man across the river watching; that there are drones up in the sky,” Karla Tait, a Wet’suwet’en matriarch and a director of programming with the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre, is quoted saying in the Amnesty report.

Other testimony from Indigenous people at the Morice River Gidimt’en Checkpoint communicate a lingering sense of fear after the police raids.

“When dogs bark at me, I just get such a physiological response. And anytime that I hear helicopters. It was really, really hard. I have lots of PTSD around helicopter sounds,” Molly Wickham, also known as Sleydo, told Amnesty.

“We’re scared,” said another person identified as Savannah. “There was a lot of fear that they would come back. A lot of people were in shock, angry, frustrated, sad and disappointed.”

Ana Piquer, Americas director at Amnesty International, described the raids as a “disturbing and concerted effort” by the B.C. and Canadian government to “remove any obstacle to the construction of the CGL pipeline.”

Ketty Nivyabandi, secretary general of Amnesty International Canada’s English-speaking section, said in a statement the forced construction of the pipeline without the nation’s free, prior and informed consent was “not an isolated injustice but part of Canada’s ongoing colonial violence towards Indigenous peoples.”

“It’s a tough lesson for our people,” said Chief Woos in an interview with Glacier Media. “The environmental concerns are still there.”

“They divided the Wet’suwet’en people. By dividing them, they pitted the Wet’suwet’en people to fight against each other, and they did that successfully.”

Pipeline companies disagree with Amnesty findings

A spokesperson for Coastal GasLink Ltd. told Glacier Media that it found “selective biases” in the way Amnesty handled information and that the group excluded “important voices” in its report.

The statement from the company said the pipeline work was lawfully authorized and went through a robust provincial regulatory process that included “extraordinary measures to meaningfully engage with all Indigenous groups.”

“At the same time, we have had to take the steps necessary to protect the safety of the women and men who worked hard on the project to provide for their families and communities,” wrote the spokesperson. “The project has faced significant acts of violence that have put people, property, and the environment at risk.”

On Feb. 17, 2022, an unknown group of people entered a remote CGL work camp with axes and destroyed multiple vehicles and equipment in an attack the company says cost millions of dollars in damage.

And this year, a group of activists said they had sabotaged the Coastal GasLink pipeline by drilling holes into the pipe in 10 locations, according to a story first reported by The Tyee.

This is not the first time Wet’suwet’en opposition to the pipeline has attracted international support.

A wave of protests and blockades spread across Canadian cities in support of Wet’suwet’en after RCMP moved to enforce a court injunction calling for the removal of any obstructions in the path of the pipeline.

In early 2020, VIA Rail traffic ground to a halt between Montreal, Toronto and Ottawa after members of the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory blocked rail lines near Belleville. One group halted train traffic coming into the Metro Vancouver on a bridge in Port Coquitlam. And another severed the route to Prince George near the B.C. town of Hazelton.

"As long as the RCMP is on sovereign Wet'suwet'en territory, the people will be in the streets fighting,” said protester Isabel Krupp at the time.

Amnesty analysis found the court injunction ultimately gave overly broad powers to the RCMP, and was applied to huge swaths of Wet’suwet’en territory not near the pipeline.

The RCMP has since used the injunction to “arbitrarily” arrest Wet’suwet’en land defenders, including for simply approaching the pipeline site, Kapron said.

Kapron said she hopes the Amnesty report will be used by the United Nations and the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights as it monitors conflict on Wet’suwet’en territory.

The report recommends the RCMP and Forsythe Security (a private security firm contracted by CGL Pipeline Ltd.) to “immediately halt the harassment, intimidation, and unlawful surveillance of Wet’suwet’en land defenders and withdraw from the nation’s territory.”

“These calls have already all been made in the past, and really, we haven't seen any response or concrete action from the Canadian government to comply with those recommendations,” Kapron said.

In the short term, the Amnesty researcher said she hopes Amnesty's findings that Wet’suwet’en land defenders were arbitrarily detained and charged moves the B.C. government to drop charges against several individuals with court dates in early 2024.

The report from Amnesty International also calls on the corporations and the B.C. and Canadian governments to halt construction of the CGL pipeline and to “fully and adequately discharge the duty to consult with the Wet’suwet’en in accordance with international human rights standards, and not proceed with the project unless they give their free, prior and informed consent.”

But given the pipeline is now complete and waiting to be commissioned, Kapron said she hopes the report spurs TC Energy and CGL to provide the Wet’suwet’en with reparations and a recognition the companies violated their rights.

“It could be financial reparations, and symbolic — I mean, this sounds maybe stupid, but like a public apology, like a recognition that there was a violation of their human rights,” she said.

“That's something that really would be determined between the government, the pipeline company and the Wet’suwet’en Nation themselves.”