UBC’s medical school is experiencing a cadaver shortage for medical students to study, researchers say as they appeal for donations.

The UBC Body Donation Program has been in operation since 1950, averaging about 80 to 110 donations annually.

However, that number has shrunk to 45-50.

And while some medical schools may be moving away from the study of cadavers in dissection and anatomy classes, for UBC medical student Armaghan Alam, the experience is critical.

“The human body is precious in its own way,” he said. “It’s important to learn things from it.”

Learning medicine with the use of a donated body is something textbooks, virtual learning or models cannot approach, Alam told Glacier Media.

“You don’t really get the detailed layers of tissues interacting with each other. You lose that certain piece of knowledge.”

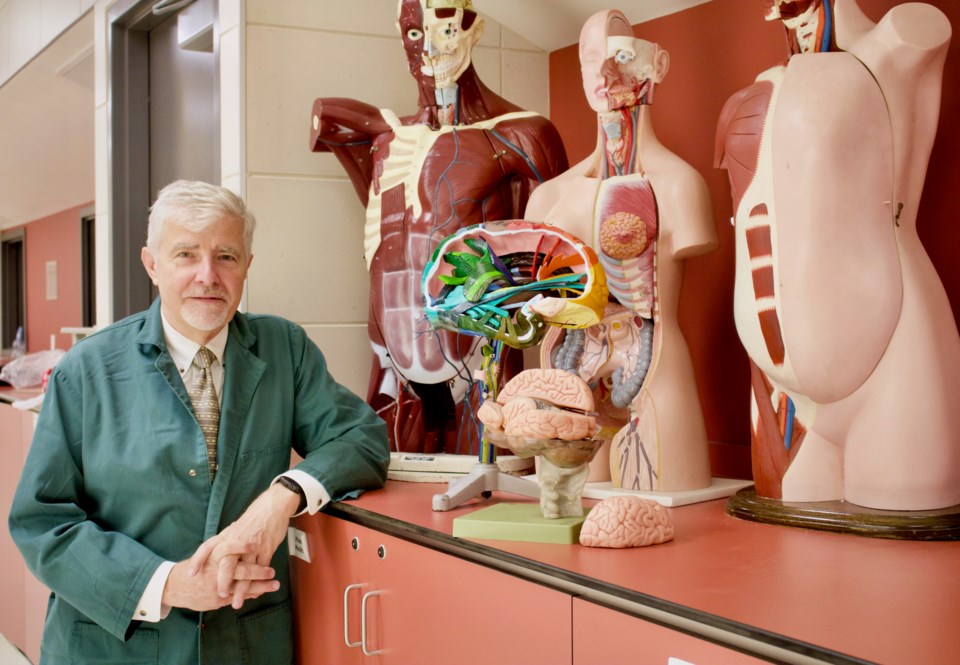

Dr. Ed Moore, professor and head of UBC’s Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, oversees the body donation program.

He said all students are told the cadavers are their first patients and must be treated with dignity and respect.

“There is no joking in the lab. No fooling around. No phones, laptops, cameras.”

Maximum education or research use is made of each gift of a body, he added. Surgeons will come in to examine new techniques, others to try such a technique before using it in the operating room.

Moore said every single donation could improve the lives of many for years to come.

“It is a remarkable gift to posterity,” he said.

Consent is key

The program handles obtaining corpses used in teaching and research. Medicine, biomedical engineering, dentistry and other students use the cadavers and tissues to learn essential anatomy, practice surgical techniques, test innovative new devices, among other uses.

Moore said donations have likely declined due to the pandemic, which saw the program shut down for a while to ensure the safety of staff and students.

Now, however, there is a need for cadavers.

Consent of the donor is a key part of the program, Moore said, noting consent can be withdrawn at any time by either the donor or their family.

“It’s entirely voluntary.”

And while past practice may have been to use unidentified bodies, that practice ceased decades ago, he said.

'A special experience for everyone'

The program stresses that students studying for careers in medicine, dentistry and related professions are respectful of donated bodies.

That respect is something Alam has returned to repeatedly.

He said when students first enter the dissection lab, it is a clinical, sterile environment.

“There’s a special kind of life that comes to the room,” Alam said. “That’s a pretty special way to celebrate the life of an individual. I think it’s a special experience for everyone.”

Alam said each body is unique and, as such, each offers unique teaching experiences for students.

He said his cadaver had a significant hernia while another had cancer. Students would learn about those conditions by looking at other cadavers in the dissection room, he explained.

Such learning situations may be on the way out at some schools, replaced by virtual teaching.

Alam doesn’t think the hands-on experience for young doctors of the dissection lab can be replicated virtually.

Referrals down

“The donation of one’s body is a very special gift to the future health-care professionals of our community,” the program website said.

“Students ... are fully aware of the special privilege granted to them and the obligation they have to conduct themselves in a professional manner during their training.

“People who donate their bodies to the medical school can be assured that all human remains are accorded the dignity and respect that our society customarily grants the dead,” the site said.

UBC officials said the shortage situation is not unique to UBC; other universities across North America are experiencing the same trend.

Each year, students organize a memorial service for donors — usually in September — who were cremated in the previous year.

Alam suggested one reason for the decline in donations may have been the lack of the physical ceremony due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A dip in referrals could be another factor, he said.

“The word of mouth may have been lost.”

Moore said anyone who's interested in becoming a donor can visit the program's website.