Scientists tracing the lifetime movements of a woolly mammoth have found her 1,000-kilometre journey from Canada’s Yukon territory to Alaska ended abruptly in a hunter-gatherer camp.

The findings, published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, offer a 14,000-year-old snapshot of life in Beringia — a region at the edge of giant ice sheets left exposed as glaciers retreated between the Lena River in Russia and the Mackenzie River in Canada.

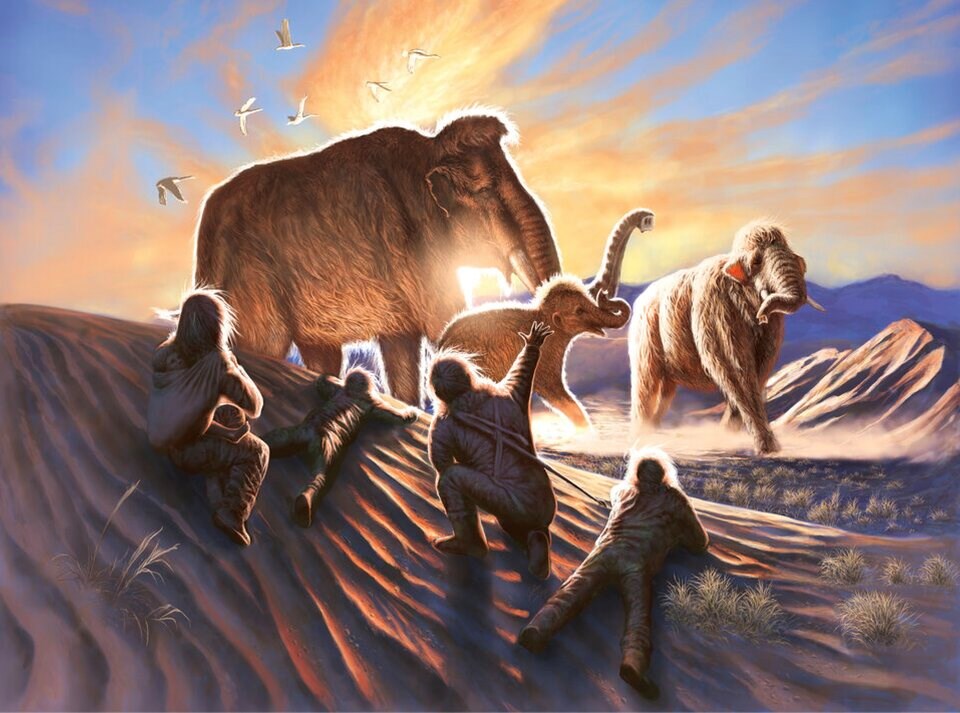

There has been limited evidence that the arrival of humans in Beringia triggered the demise of mammoths — what archaeologists in the field call the “blitzkrieg overkill scenario” — or whether their extinction was the result of a shift in climate and plants mammoth survived on.

The latest study, however, suggests humans likely stalked mammoth into modern Alaska as they sought out grazing grounds at the end of the last ice age.

“It seems that maybe humans were utilizing the same area because it was a hotspot of mammals and other large grazers,” said lead author Audrey Rowe, a PhD student at University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Human hunters had 'means and motive'

Twenty researchers took part in the study from across Canada and the United States. Together, they carried out an isotopic and genetic analysis of the female mammoth’s tusk, using its chemical makeup to understand where and how she lived.

Healthy at the time of her death, it’s not clear how the roughly 20-year-old creature died in late summer, about 1,000 kilometres away from where she spent the first part of her life.

Rowe said the mammoth’s movement through the White Mountains suggests her herd was in search of better grazing grounds. By then, woody shrubs would have begun invading the river valleys of the ancient step grasses, fragmenting mammoth habitat into patches more easily exploited by potential human hunters, the study says.

Her remains were found in Alaska’s Tanana River valley next to two closely related younger family members, among hundreds of other mammoth remains. Rowe said archaeological evidence also shows the humans in the nearby camp had tool kits that matched those of human groups in Siberia.

“There's this really famous archaeological site in Siberia where there's micro-blades literally embedded in a mammoth spine — smoking gun. That mammoth was hunted. And if these people at one point had the exact same technology, I think it's almost condescending to assume that they could not have hunted mammoth,” Rowe said.

“I like to say that we have means and motive established here.”

Discovery comes amid a rush to 'de-extinct' woolly mammoths

The study comes at a time when Rowe said there has been a resurgence of interest in woolly mammoths, something she links to the production company DreamWorks for its Ice Age movies.

“There was like dinosaur fervour for a while. That seems to have moved on to ice age fauna,” she said.

One company, Colossal Laboratories and Biosciences headquartered in Dallas, Texas, has even launched a “de-extinction” program that seeks to use mammoth DNA to genetically engineer a living cold-resistant elephant.

“By de-extincting the core genes and engineering the physical characteristics of a lineage lost to extinction, Colossal will equip species with enhanced adaptability to new climates, drought tolerance and resilience against disease,” notes the company.

Rowe said whether such a course of action is wise is up for debate. But in the meantime, understanding how humans and woolly mammoth interacted offers practical lessons if the species is eventually brought back to life.

Perhaps more important, she said, the research shows how close modern humans are to a people that lived in an environment we will never truly know.

“We think of them as, you know, like these primitive cavemen a lot of time… like the intro scene to 2001: A Space Odyssey,” she said. “But they were us. They were super advanced people who had amazing technology to be surviving up in these really harsh habitats and to be able to create weapons that can hurt mammoths.”

“That we as modern people are never going to be able to see that, it's kind of bittersweet to me.”