It’s a clash of viewpoints, perhaps even values, and it’s only going to get louder in Delta.

The much talked about housing crisis in the Lower Mainland is a daily news item nowadays and Delta is far from immune as familiar arguments over introducing higher density in established single-family neighbourhoods rage seemingly with almost every new application.

Largely developed a half-century ago following the opening of the George Massey Tunnel, Delta has become an enviable place to live thanks to quiet, tree-lined streets and its small town feel despite being in the shadow of a major metropolitan centre.

However, its single-family-centric housing stock is not only getting old, it’s also out of reach price-wise for many people, particularly first-time buyers, which has turned up redevelopment pressures and created flashpoints throughout the community.

Gordon Price, the former director of The City Program at Simon Fraser University and former six-term councillor in Vancouver, knows all too well the challenges communities and governments are facing.

Price acknowledges the neighbourhoods created by single-family housing in Delta are desirable, but points out that all of the available land for the urban form has basically been used up.

“The people that are in that housing like it that way, and I understand why,” he said. “I do think you can make a good case that the post-war era of single-family housing and all the related services and growth of that time was maybe the best human beings have ever had it.”

He said the housing stock of yesterday is not appropriate for today, but trying to find balance is a constant battle.

“You can look at it from that social aspect and what are the housing needs we need now, but behind that is this set of assumptions that government should be able to use its tools to ensure that there is a sufficient quantity of housing and you can get into a discussion of what the housing should be without inducing scarcity, but government isn’t operating on that assumption in places like Delta,” Price said.

“It’s not a case of mass rezoning, you can change it with just a handful of policy instruments and we have actually seen that in real time with what the NDP and the City of Vancouver did with bringing in some policy changes.

“At that point when the market was saturated with very expensive housing it didn’t take much for that to change, so it may be, and I’m speculating here in Delta, that it wouldn’t take too much in the way of change to address what seems to be the social issues you are trying to address – affordability, homelessness, seniors.

“It’s all based upon the assumption that there should be some change in the scale and character of existing neighbourhoods to provide options for people that they currently don’t have or won’t have in the foreseeable future and that is the political question.”

The latest round in the redevelopment battle played out in late May at the corner of 8A Avenue 53rd Street in Tsawwassen as Maple Leaf Homes proposed building 37 townhouses in what has been, until now, strictly a single-family area.

Several speakers in opposition argued, among other things, the project is too dense and doesn’t fit with the neighbourhood character, while supporters, including some connected with the developer or real estate industry, talked about the need to introduce more affordable housing stock.

Delta council voted 6-1 in favour of the rezoning application.

Concerned more neighbourhood-altering developments are coming, Tsawwassen resident David Trotter started the Tsawwassen Action Group.

Trotter said one of the group’s goals is to get more residents engaged and make sure their voices and concerns are heard.

“The group is not anti-development,” he said. “I think we all acknowledge that we need to do a better job with housing that is affordable for young people and do something for the seniors. I think our complaint about the 8A (Avenue) piece was that it didn’t seem to accomplish either. You have townhomes that will be between $800,000 and $1 million and they are three storeys, and combining that with the fact that is doesn’t fit in with the surrounding neighbourhood, it seemed to be a challenge.”

Trotter said neighbourhood planning should centre on questions like: Can you have more duplexes and four-plexes? Can you make it easier to have a legal suite? Can you look at things similar to lane-way homes in Vancouver?

“The group would like to see housing options that are not just all about destroying a fabric of a neighbourhood,” he said. “It’s trying to find that balance in knowing there is a need for more density, but having it fit in with the community and actually solve the problem. If you look at the development mantra on these projects, it is all about young people and seniors yet none of the projects hit young people and seniors.

“As a community, we all need to get together on the same page. We need better dialogue with developers and we need to work more closely with council on what is fair and we need to be well-organized so our voices are heard.”

What the pro-development side is quick to point out is that, according to Delta’s Social Profile, single-family homes and duplexes still make up 80 per cent of the city’s housing stock. With condos around 14 per cent and townhomes at just 5.5 per cent, they say that has created a lack of affordable options.

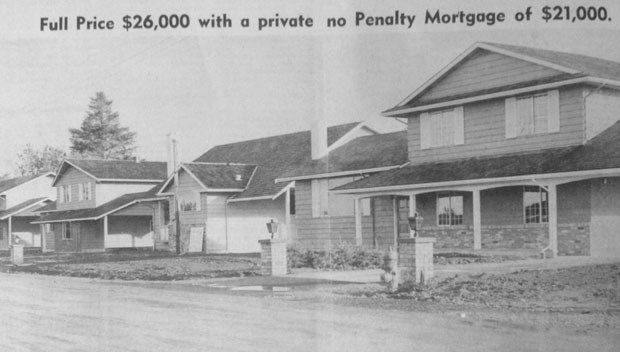

Fraser Elliott, who heads the number one real estate team in South Delta for the past nine years, said the single-family zoning that’s prevalent in the area is based on the 1960s when Canada’s population was less than half it is today. He said the housing demand being created by increased population across the board requires zoning changes.

With bare land virtually non-existent, and farmland rightfully off limits, Elliott believes redeveloping single-family areas is the only choice to meet demand. He points to areas adjacent to town cores where higher density already exists as logical spots to rezone.

First elected to Delta council in the early 1970s, and having served 19 years as mayor before being elected again as a councillor last fall, Lois Jackson said when much of Delta’s housing was built it met the needs of the most of the population at the time, but what wasn’t anticipated was a regional population boom. Metro Vancouver’s 2016 population of 2.5 million is anticipated to increase by about one million by 2050.

“Where are they going to live? Now what we’re seeing is a lot of infill redevelopment where they’re spitting lots and building two smaller houses where there was just one, especially here in North Delta, but are those houses really affordable? Are those houses going to solve the issue of affordability? You’ll see more basement suites for rent, but that’s about all,” Jackson said.

Over a decade ago, prior to the explosion of housing prices in the Lower Mainland, the city put together a housing task force that came up with a number of recommendations, most of which were approved, including legalizing secondary suites. In a 2008 interview, task force chair Scott Hamilton at the time wouldn’t go so far as to describe the situation as a crisis, but acknowledged a need for more housing for people of all ages.

"What's really important is there needs to be a level of acceptance that has to be achieved by a neighbourhood and a community as to what they're prepared to invite into their community and how they want to see it evolve," said Hamilton.

A recent poll of 1,001 British Columbians carried out by Ipsos for the Urban Development Institute found respondents in widespread support of new housing forms in traditionally single-family neighbourhoods. Seventy-four per cent believe home prices and rents remain high because there are too few housing options, while 70 per cent believe the actions of governments have not improved housing affordability.

UDI president and CEO Anne McMullin noted townhomes are becoming out of reach for many entering the market due to a limited supply in Delta and throughout the region.

“I totally understand that people want to maintain the character of their single-family neighbourhoods, but at the same time they have to realize our region is growing. We need to think more broadly as a community and talk about the benefits of growth. How do these people have homes?

“My view is that the best community is one that is diverse and has a diversity of people, of income levels, family makeup, but the only way to do that is to provide a diversity of housing options, rather than always fighting against higher density and development,” McMullin said.

According to the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, a detached house in Ladner went up over 80 per cent over the last decade. For a while, the Ladner benchmark surpassed the $1 million mark, although it’s now slightly below that level. The benchmark price during that time in Tsawwassen doubled and is currently just under $1.2 million.

Metro Vancouver’s 2019 Housing Data Book notes a home is considered affordable if a median household income can purchase the unit with 10 per cent down and a 25-year amortization period, and pay no more than 30 per cent of their income. Based on these considerations, according to the report, the estimated affordable price of a unit is set at $420,000.

However, the report notes that in 2017, only 18 per cent of sales of all unit types in the region were considered affordable, a decline from 32 per cent in 2010.

A Delta civic report found that while there’s been a significant influx of housing in recent years, the additional supply is not curbing rising unaffordability.

“Reviewing the number of affordable sales between 2012 and 2017, the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver reported that, in Delta, affordable apartment and condo sales fell from 79 per cent of total sales in 2012 to 56 per cent in 2017; affordable townhouse sales fell from 22 per cent to six per cent; and affordable single detached house sales fell from one per cent to 0.5 per cent. This barrier to attainable ownership also places additional strain on the rental housing market as those who would otherwise own continue to need rental housing.”

Ron Rapp, CEO of the Homebuilders Association Vancouver, said most people either want a single-family detached home or row home/townhome as their first home, but that’s now a challenge.

The increasing population and lack of land means prices will only be going up, which means smaller units are first-time buyers’ best hope of getting into the market, especially with new, more stringent “stress test” mortgage requirements.

“To some degree, the existing zoning and planning protocols don’t necessarily support what I would call creative solutions when we are trying to come to terms with these costs. The traditional ratio of what your shelter should cost used to be in the order of about 33 per cent of your gross monthly income. Well, at this point, what kind of price correction would we have to see to be able to regain that kind of ratio? It would be catastrophic,” said Rapp.

“So, there’s really only one way for us to be able to move forward and that is to be able to come up with innovative, more creative ways to be able to create at least gentle density, if nothing else, to be able to provide more housing options for the greater population, in particular the first-time buyer. It’s that group of people we need to be able to get into the marketplace by hook or by crook because without those first-time buyers coming into the marketplace, there is no sustainable market.”

The City of Delta has approved Official Community Plan changes for major corridors to allow higher density, including areas like Scott Road, where high-rise proposals are now appearing, and 72nd Avenue, where a couple of townhouse complexes are being built and several land assemblies are in the works.

A major project that could include high-rise buildings, although not to the extent of what’s proposed for Scott Road, is being eyed by the Century Group as it looks to redevelop the Tsawwassen Town Centre Mall. Meanwhile, next door at the Tsawwassen First Nation, a mix of single-family, townhouse and condos are being constructed, which will bring about 8,000 new residents once complete.

This year, Delta council gave the go-ahead to develop a housing action plan. According to staff, while Delta has strong policies surrounding housing, it has not had an action plan to help set priorities.

“Delta lacks the spectrum of housing options and tenures needed to accommodate the projected demographics and needs of residents, particularly young adults and seniors wishing to stay in their community,” a civic report states.