Kingsway is one of Vancouver's most important roads.

Cutting from just outside the city's downtown core all the way to the southeastern border of the city and through Burnaby, it's lined with businesses its entire time in Vancouver, making it an important commercial thoroughfare.

Not only is it a significant route nowadays, but it's a road that's been important since before the city existed (more on that in a second).

1. It's hundreds of years old, if not older

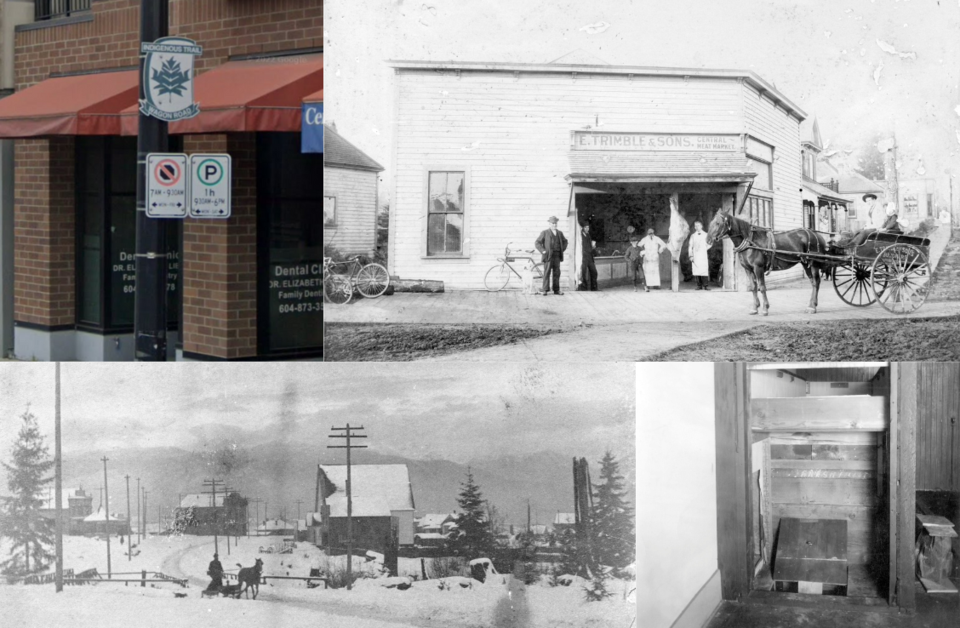

People were using the route now known as Kingsway long before European colonizers arrived in the area. In fact, it was likely being used before European settlers arrived in North America.

First Nations villages existed throughout the region, and the path is a sensible route between Burrard Inlet and the Fraser River before it splits around what is now called Lulu Island.

2. It was originally named after New Westminster and was renamed with a parade

As New Westminster was the major town in the Lower Mainland for decades, the road that went there was called Westminster Road.

It was used to move people from Gastown, once it started to grow, to Westminster, which was the capital of the Colony of British Columbia until it amalgamated with Vancouver Island. And even then, New Westminster was the most significant city in the region for some time.

In 1913, the road was paved and renamed, becoming a sort of precursor to a highway (cars were relatively new and slow).

To celebrate the renaming of the road, it was inaugurated with speeches by the acting-premier and a provincial minister. There was also an "automobile parade," as one newspaper put it, and a luncheon at the border of Burnaby and South Vancouver (which was a separate city at the time).

Notably, not everyone was happy with the paving of the road, as it was expensive (the city paid for the bulk of it, but landowners along the road had to pitch in as well) and allowed faster driving. One dog breeder, according to the Daily Province, sold three of his top dogs to someone in Albuquerque, New Mexico, because of the "increasingly dangerous traffic" along Kingsway.

3. It was the site of an unusual attempted robbery

The address of 666 Kingsway may sound cursed, and for some it was (sort of).

A group of would-be robbers decided they wanted to rob the Royal Bank that was located there circa 1936, so they set up shop at 662 Kingsway—almost literally.

They made it look like they were enterprising mushroom growers and then started digging a tunnel.

The goal was to tunnel under the dry cleaners that sat between the bank and their spot and sneak into the bank.

Unfortunately for them, they were caught in the process.

4. There used to be bridges

Kingsway may seem like a fairly straightforward road now, but that's a long time coming.

At one point Vancouver had many creeks that cut through the land; one of the major ones was Brewery Creek in Mount Pleasant; it provided water and power for breweries and other businesses in the neighbourhood's early days.

Before the area was transformed, there were several bridges over the creek, including one for Kingsway near Broadway (there's a marker there now).

5. Signs along it are actually art, not for a highway

Those who use Kingsway on a regular basis will probably recognize the signs along it that say "Indigenous Trail Wagon Road."

While they look like street signs akin to the Highway 1 signs across the country, they're actually public art installed in 2012.

"As an urban Indigenous person calling Vancouver home for many years, I wanted to honour the First Peoples history and Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations with my work," reads artist Sunny Assu's statement about the piece.